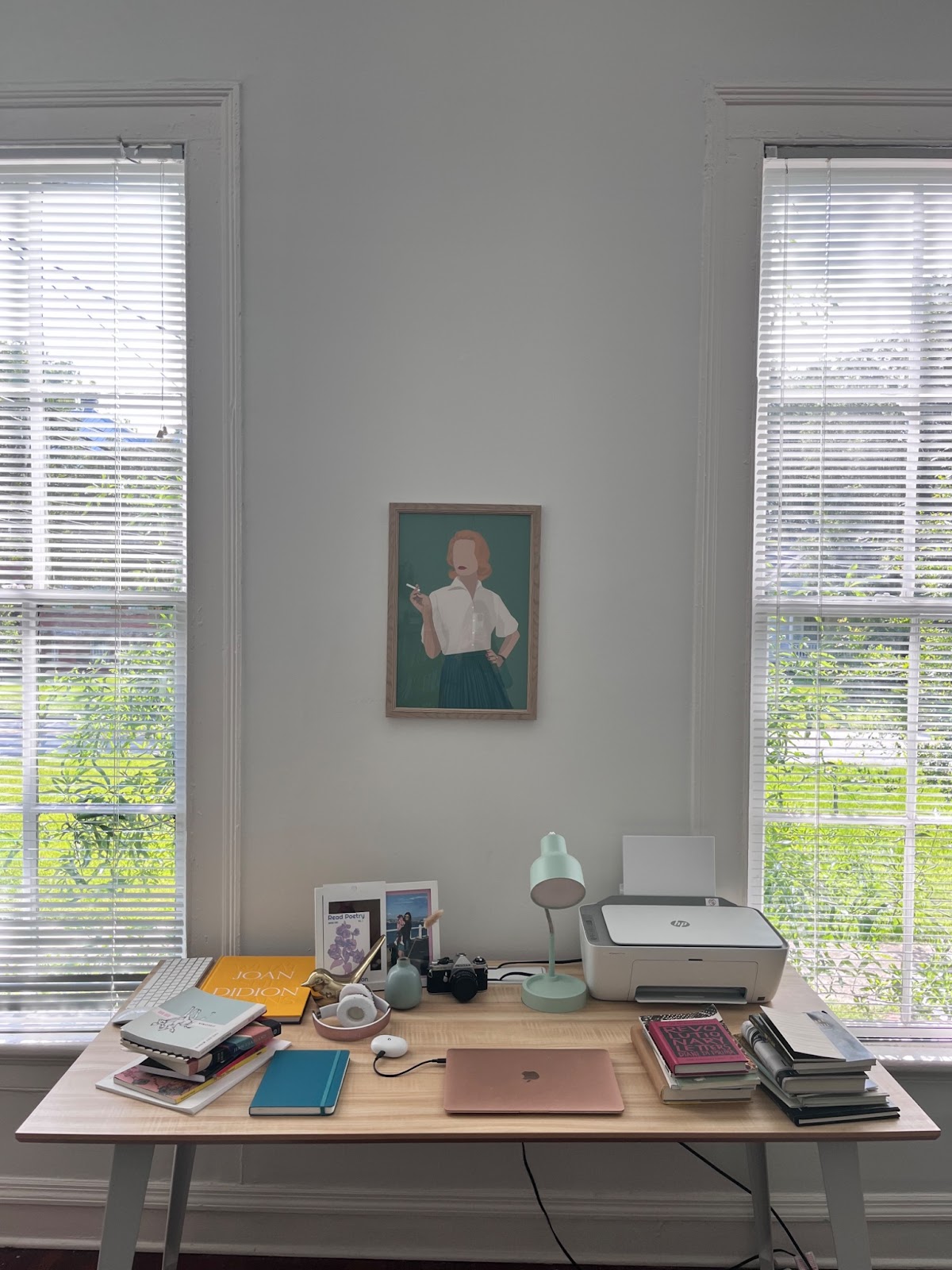

I’ve had many desks—oaken and heavy, spare and intentional, cubicled and shared. They’ve stood in Soho, overlooked San Francisco’s Battery Street, and were perched in Oakland’s Tribune Tower. Once, I even sat with my back to the Potomac at The Watergate, turning now and then to catch the glint off the river’s blue. But only now, at 39 and five years into freelancing, do I finally have a desk that’s mine, and not just a surface to work on, but a site of real accumulation—a place to layer, collect, and make meaning. It’s where my commercial writer and poet selves sit across from each other, ideating over the same mug, scribbling in the same notebook, pulling from the same stack of books and postcards and prints.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about what gathers on a desk—and how ordinary objects become biographical. We all know words hold more than letters—they carry connotation, texture, tone, but so do the things we keep close. In semiotics—the study of signs, objects are never just functional. As Roland Barthes suggests, they’re loaded with private mythologies, cultural shorthand, and social residue.

Projects like The Burning House and Vogue’s The Bag get it: objects matter. The Burning House—a once-viral photo series that asked, “If your house were burning, what would you take?”—showcased items both curated and beloved: a stuffed squirrel, a roll of old film, an OP-1 synth, a passport. The Bag, on the other hand, trades in the real (or, at least, the aspirational), peeking inside celebrity totes to reveal Theragun minis, Laneige Lip Glowy Balm, gummy bears, and knitting needles. One is imagined, the other lived—but both reveal something deeper: how we make the intangible visible through what we choose to carry, display, and keep close. The bottom line is these snaps, still lifes, keepsakes—they tell our story.

That idea—that objects are not inert, but saturated with significance—has stayed with me. And it’s made me rethink my desk as a lens into the ways I work, who I am, and why.

So, what's on (and above) my desk? And, what do some of the objects say about me both as a freelancer—naming and strategizing and writing commercially—and as a writer's writer—writing and editing and publishing poems, essays, and more.

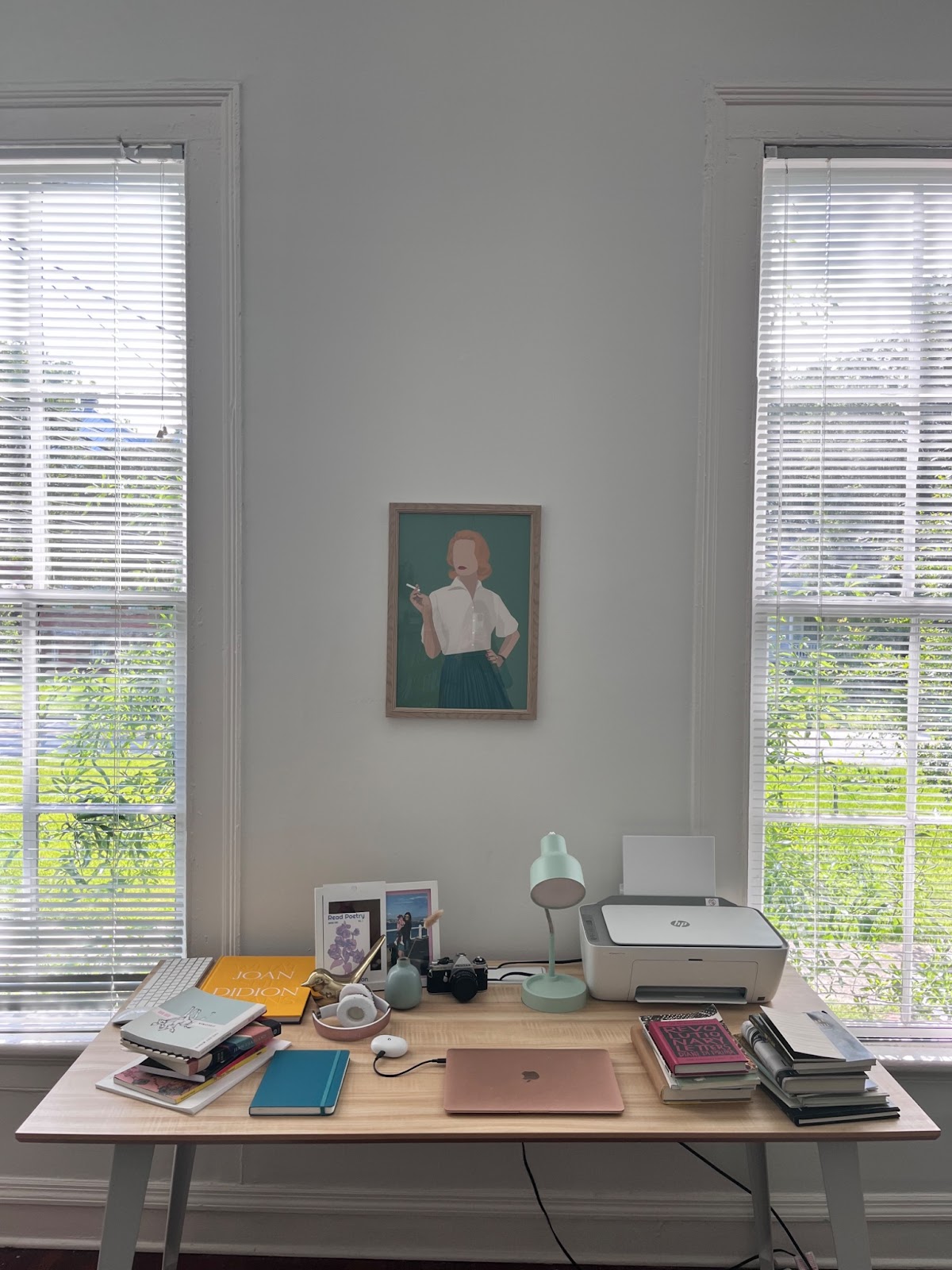

Betty Draper print

Back in my early 20s, I was studying brand strategy and copywriting at NYU while working in publishing—and Mad Men was the show. Then, Peggy, the lone female copywriter on Madison Avenue, was my north star. These days, as a mother with Rao’s pasta sauce in my hair and Google Calendar rage in my heart, I relate far more to the cigarette-wielding Betty. And in this particular print, Betty is eyeless and noseless, perfect. She’s also likely a stand-in for my long-running obsession with women in fragments, which probably began when I first saw Guy Bourdin’s Walking Legs, a Charles Jourdan campaign that starred disembodied mannequin limbs in heels. Back then, I found them eerie and oddly captivating. Now, they, like my Betty print, remind me of the mother I am: part, parceled, looked at but never fully seen.

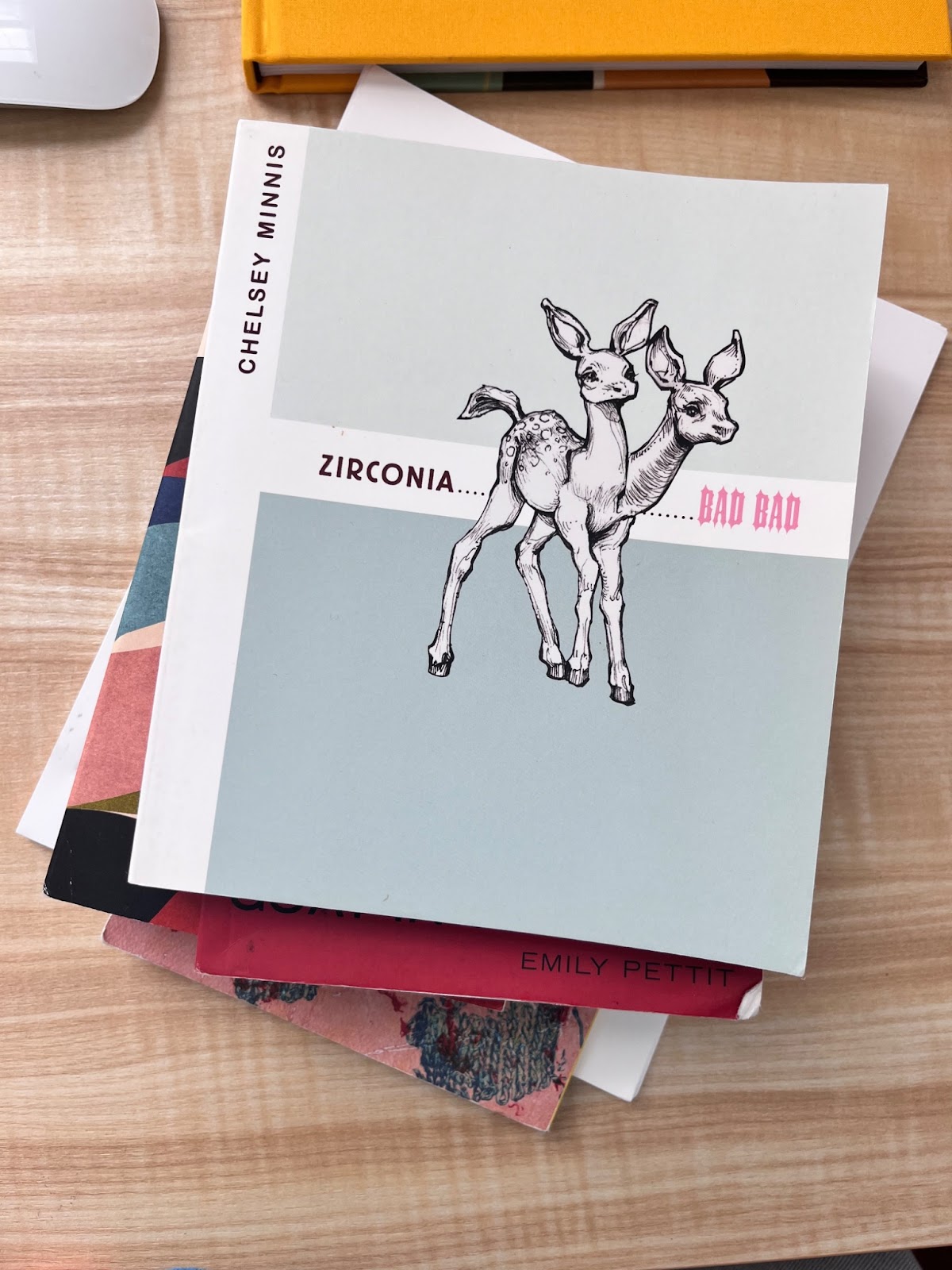

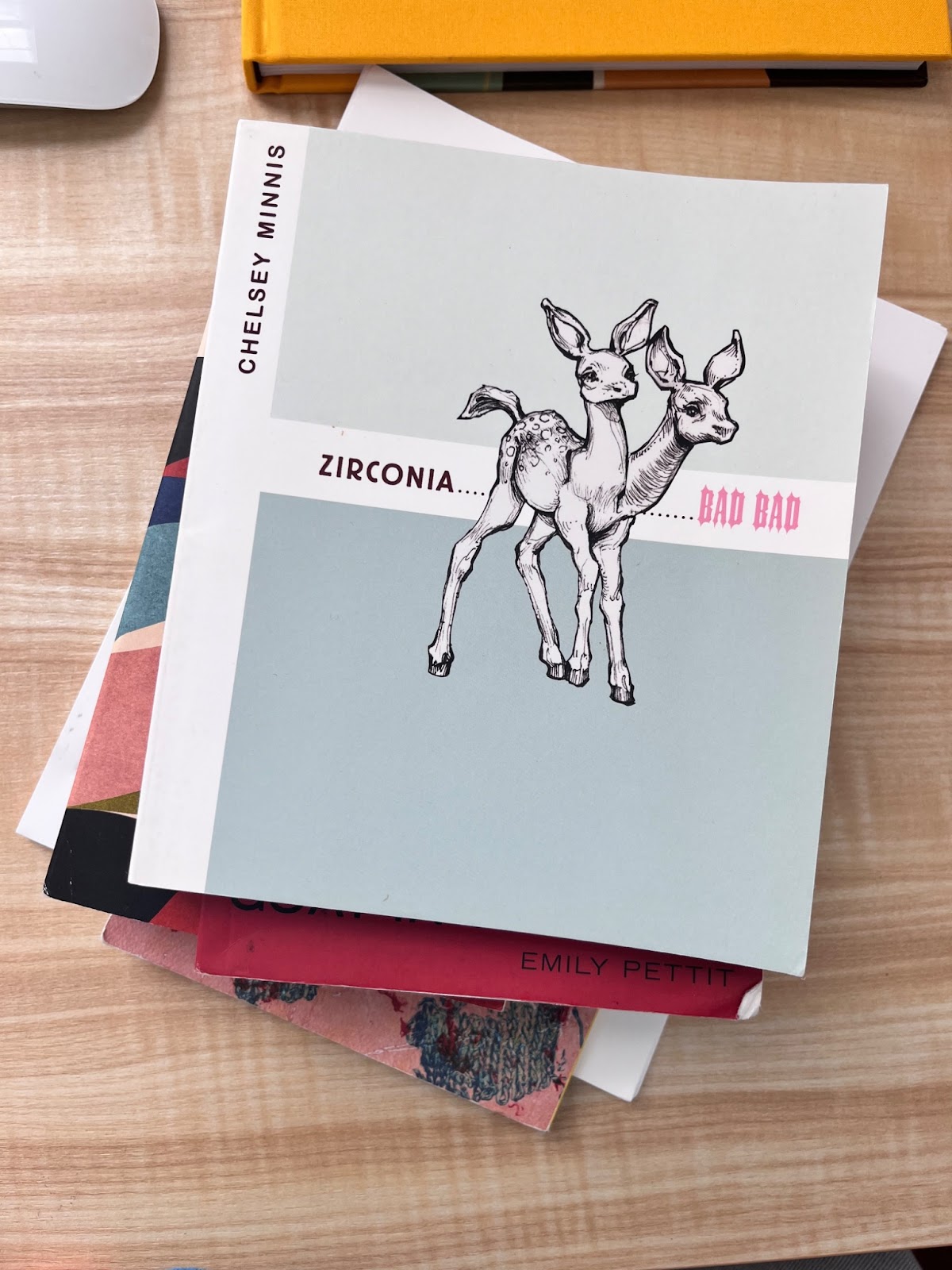

Zirconia & Bad, Bad, Chelsea Minnis

Copywriters, take note: poet Chelsea Minnis is the queen of voice and a perfect reminder that the writer and the speaker are not the same thing. I turn to her when I need to slip into something more operatic—a feather boa of an “I,” all sequins, fur, and chaise lounges. In certain collections, her voice is really something to behold: over-the-top, glamorous, exaggerated, clichéd, and gloriously camp. And, yet, beneath the jewels, mink, and champagne flutes? There exists real truth.

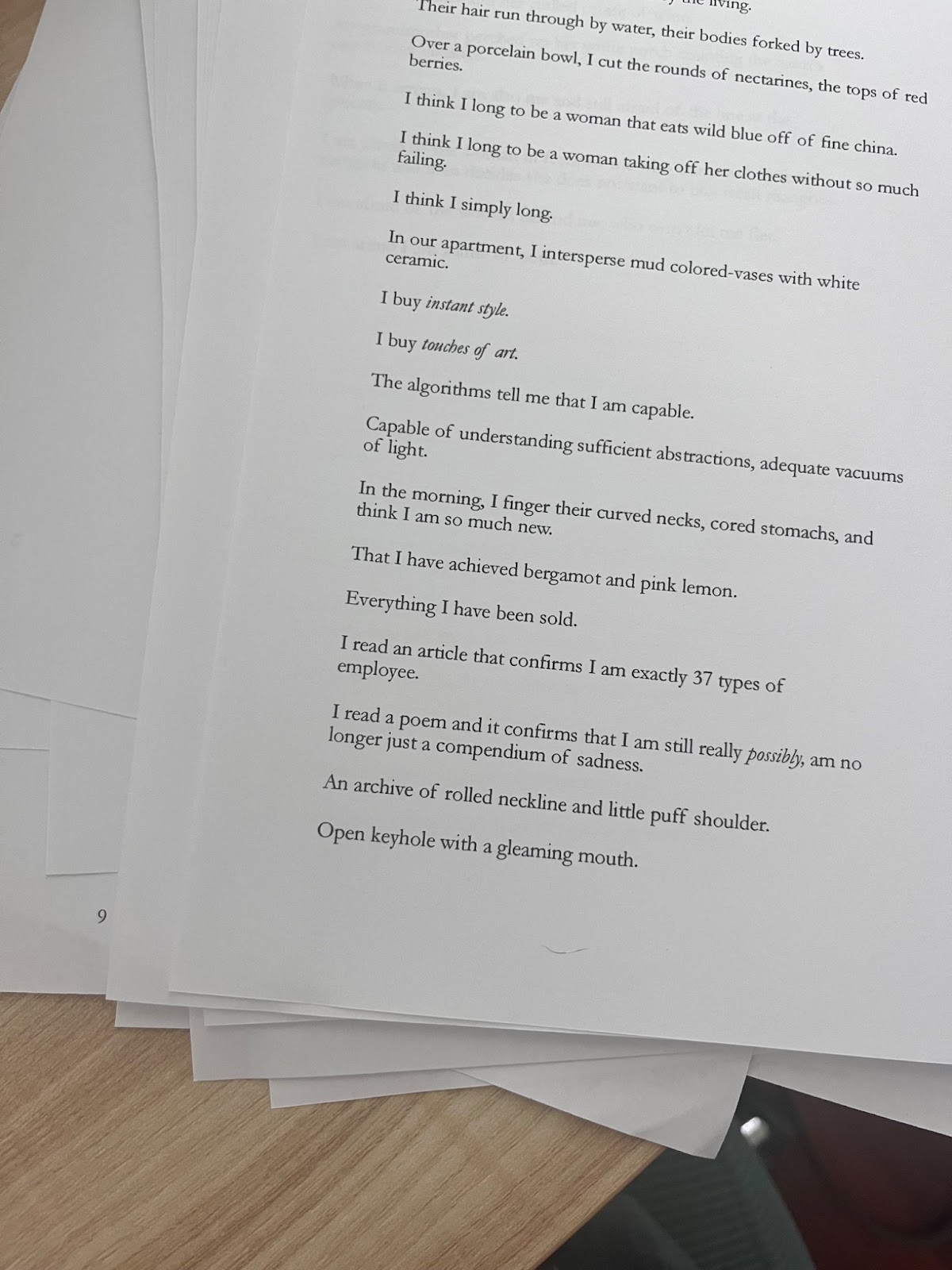

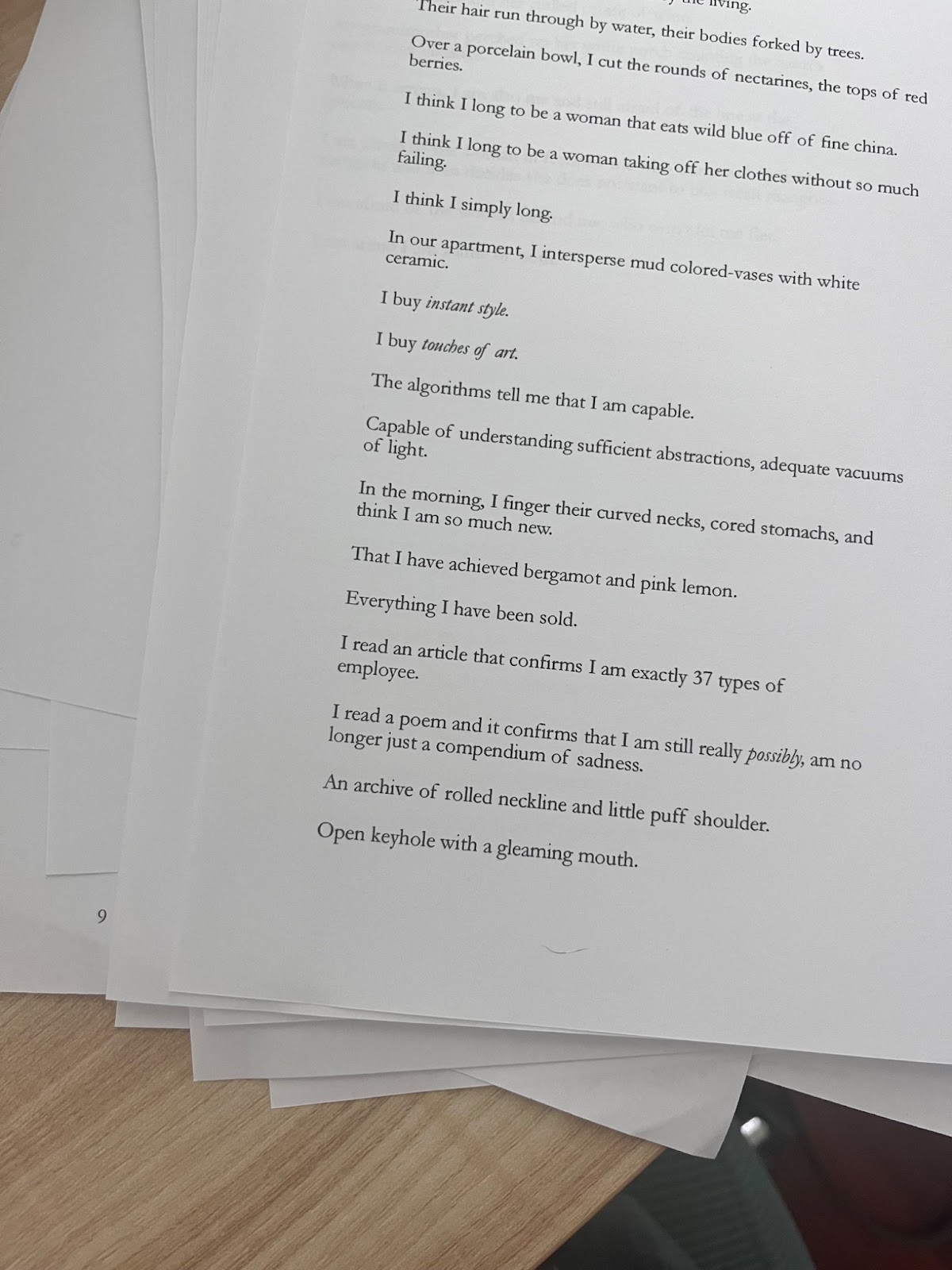

HP DeskJet 2755e

I hadn’t touched a printer at home since I worked as an editorial assistant in NYC. After swearing off all glorified-secretary roles, I was certain I’d never need one again. Then came poetry, ready to prove me wrong. Now, as an editor with the press blush lit, I spend weekends printing out manuscripts and reviewing others’ collections. The rest of the time, I’m printing my own. This printer’s current job? Spitting out drafts and drafts alone. The below image showcases a poem from one of two manuscripts I am currently surfacing with presses, Full Bleed. And yes, the printer drinks ink like a fiend.

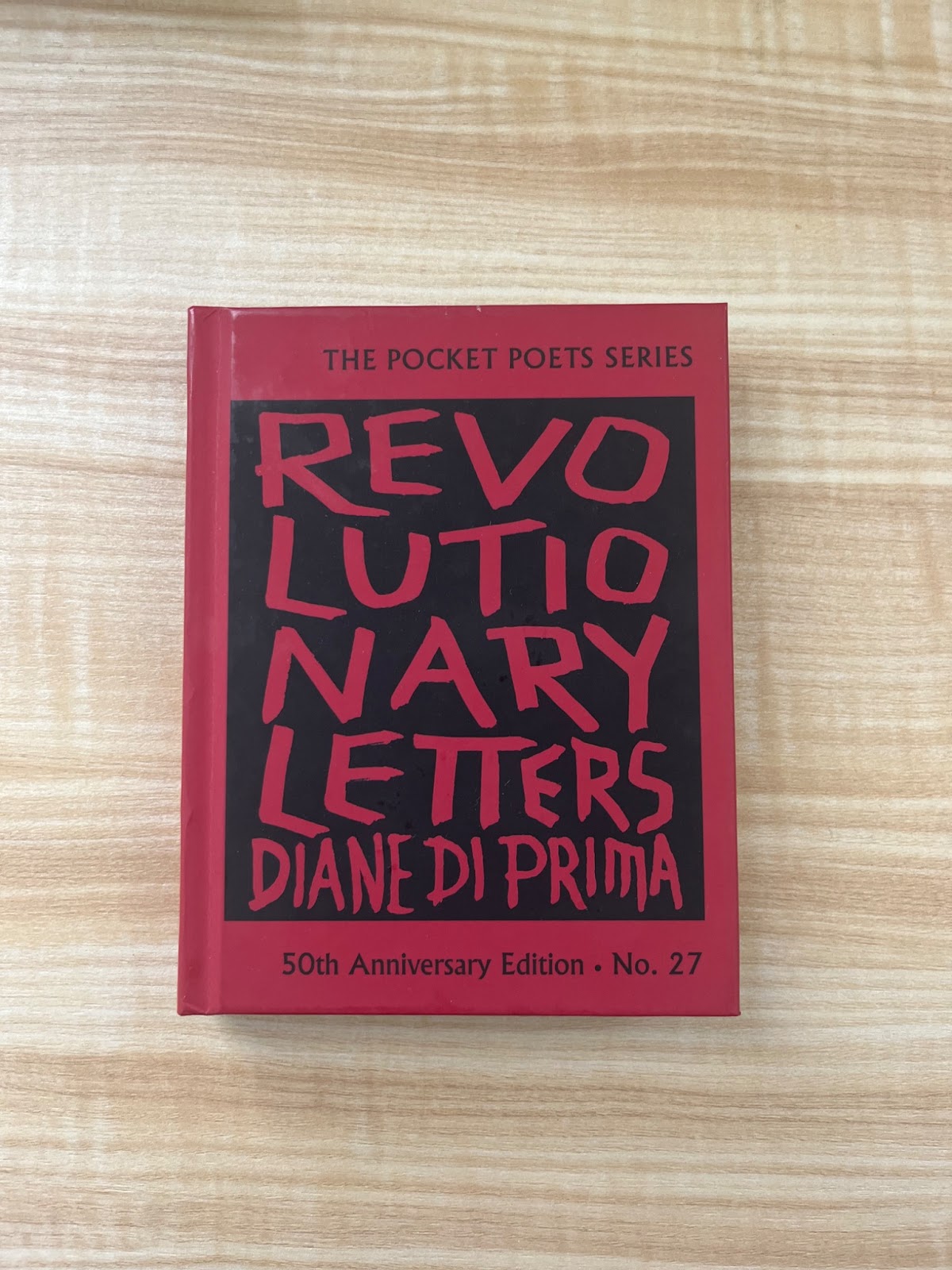

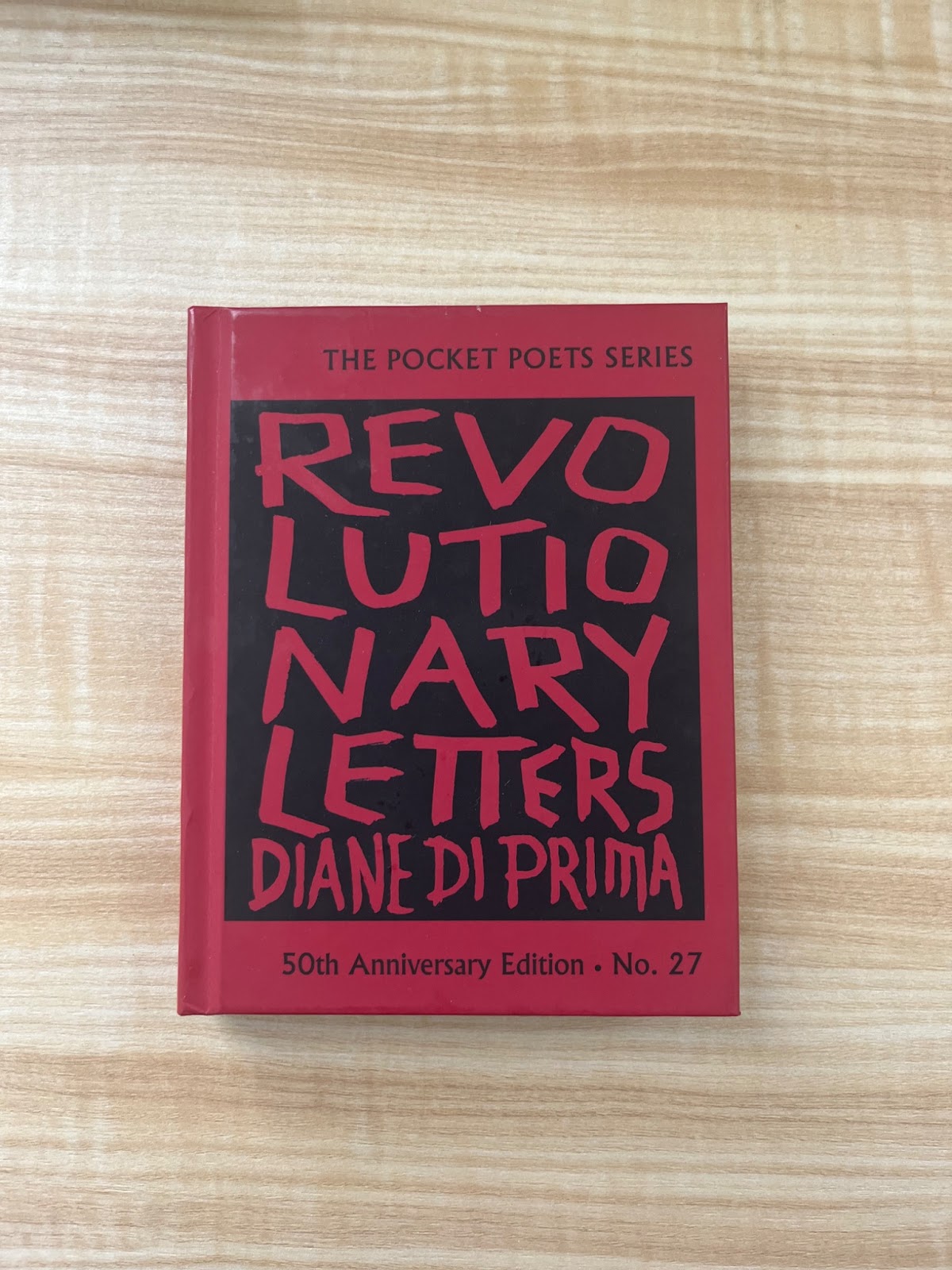

The Revolutionary Letters, Diane Di Prima

Some people have burn books. Some people have little black books. Other people have tiny red books—specifically this one. BEAT poet Diane di Prima first published this tiny pocket of poetic resistance with SF's City Lights Books in 1971.

Don’t read if you’d rather not critically interrogate your role as a knowledge worker in late capitalism.

Do read if you're ready to rethink the brands you write (and name) for, the clients you valorize, and the ways in which you show up in the world.

The Nondescript Bird

Chekhov has his guns, and we poets and namers have our birds: Twitter, Hootsuite, Nest, Thunderbird, Golden Goose, Bluebird Bio, Albatross Designs, Redhawk Wealth Advisors.

Need I say more.

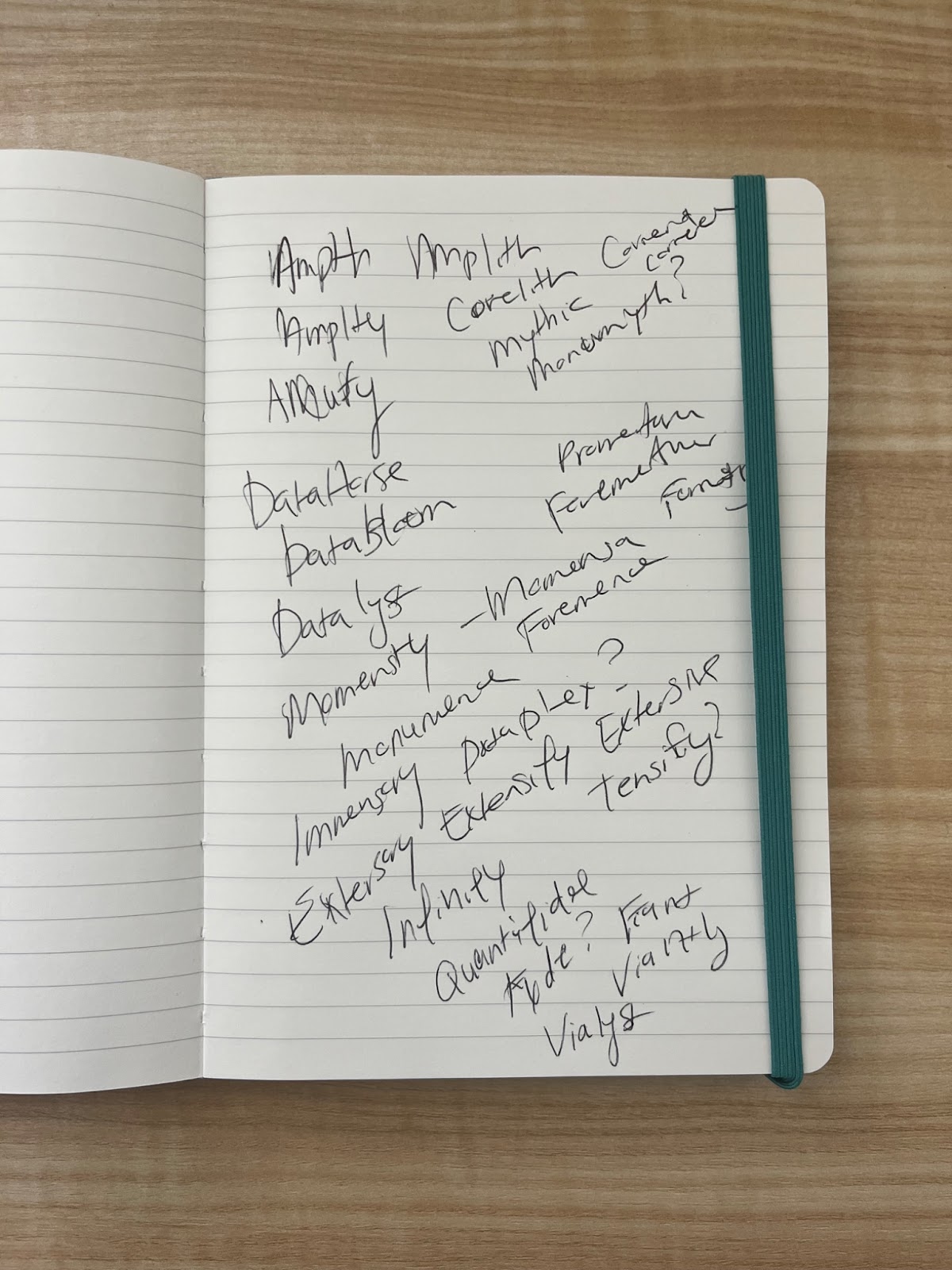

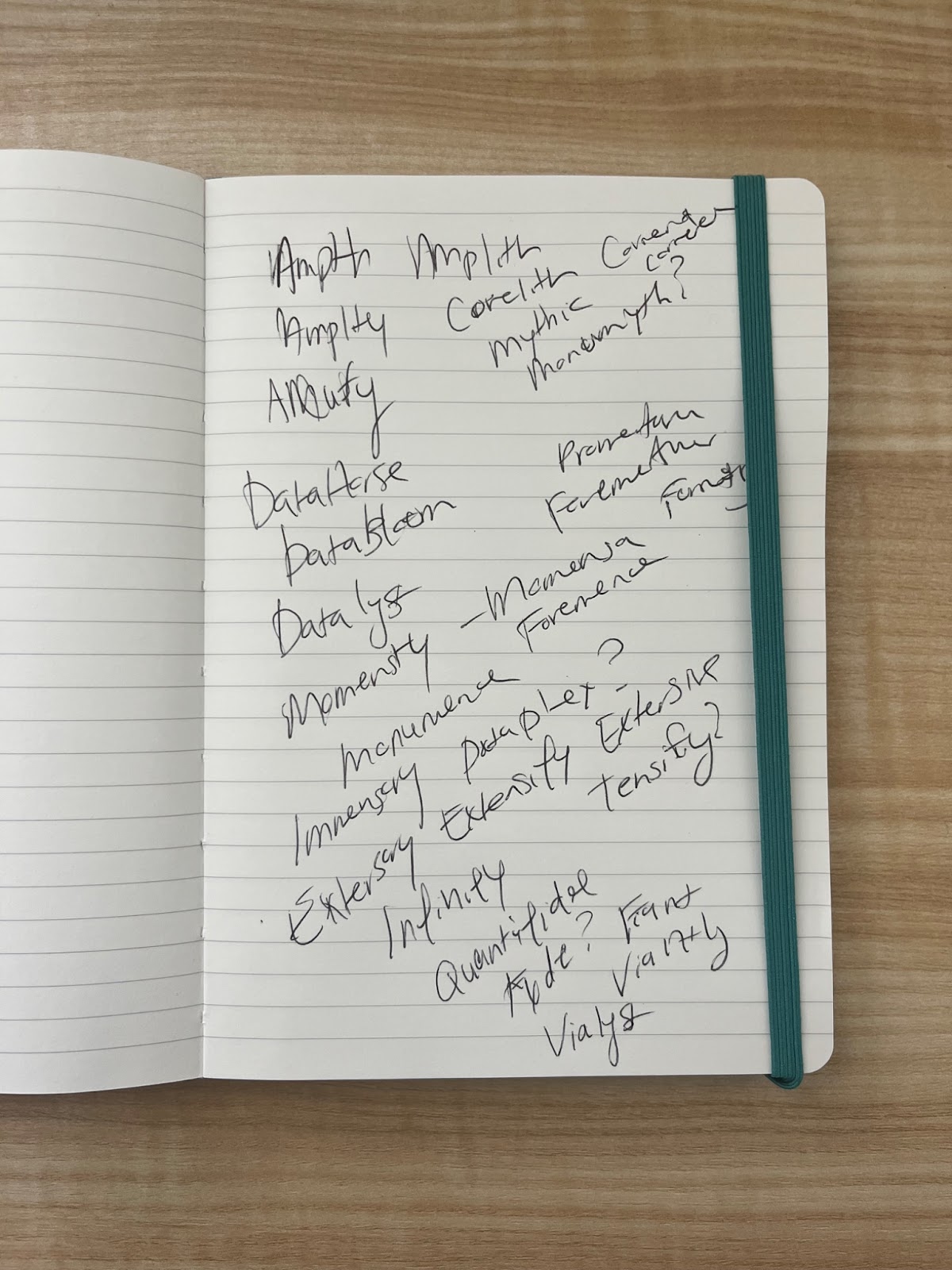

Notebook (unknown origin, aquamarine)

I find I do my best writing in the morning, and following a Maker's Schedule, I like to keep my 9 AM - 1 PM EST blocked. But when it comes to naming? My best work happens somewhere between dreaming and the not-quite-awake state. It’s known that sleep helps us organize ideas and make sense of our days, but it’s that moment before or after total darkness—the slippery in-between—where magic happens for me. My little lined notebook goes to bed with me every night and shows up to work with me every morning, usually peppered with name ideas, looping thoughts, and rabid iterations.

Pentax ME Super

I bought this used Pentax ME Super a few years ago because the places I’ve lived have always felt generative. From photographing container ships along the Columbus River and the sky purpling behind them to capturing the sea edged in by palm fronds in the Keys, I started a kind of visual journal of my life. With time, though, I began seeking out not just documentation but Barthes’ punctum—that thing which wounds, pierces, stings. The absurd. The uncanny. The ironic. A toy Pumba lodged in a cement pole, a half-submerged candy cane in a resort pool, birds gathered at a gas station—one performing a monologue from a telephone line. That's when photography turned for me, and I saw it as a way to express irony, cynicism, and dystopic feelings through the world I alone framed. And, the walks I take? They’ve proven essential for my writing and thinking and ideating, my meaning making.

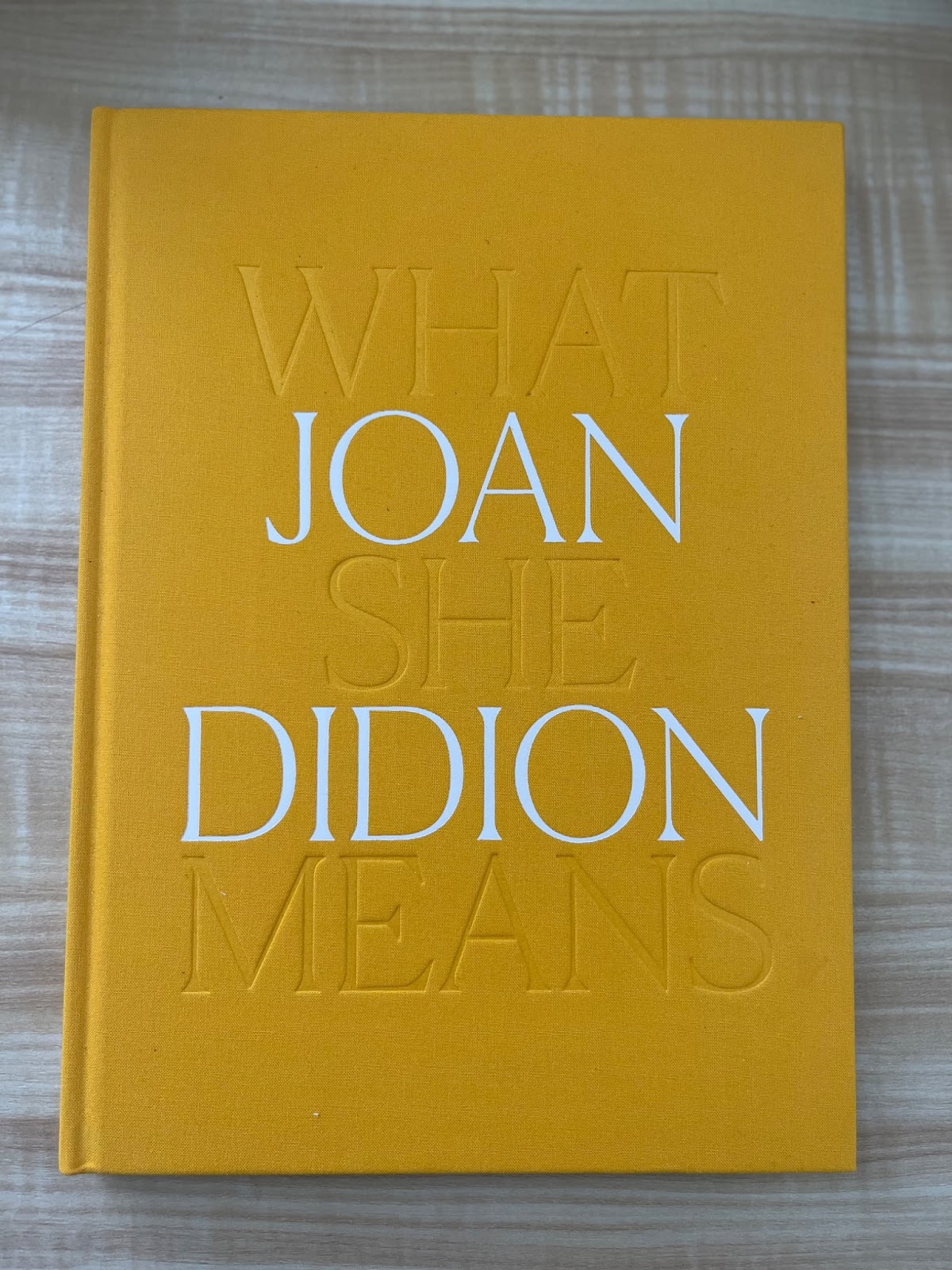

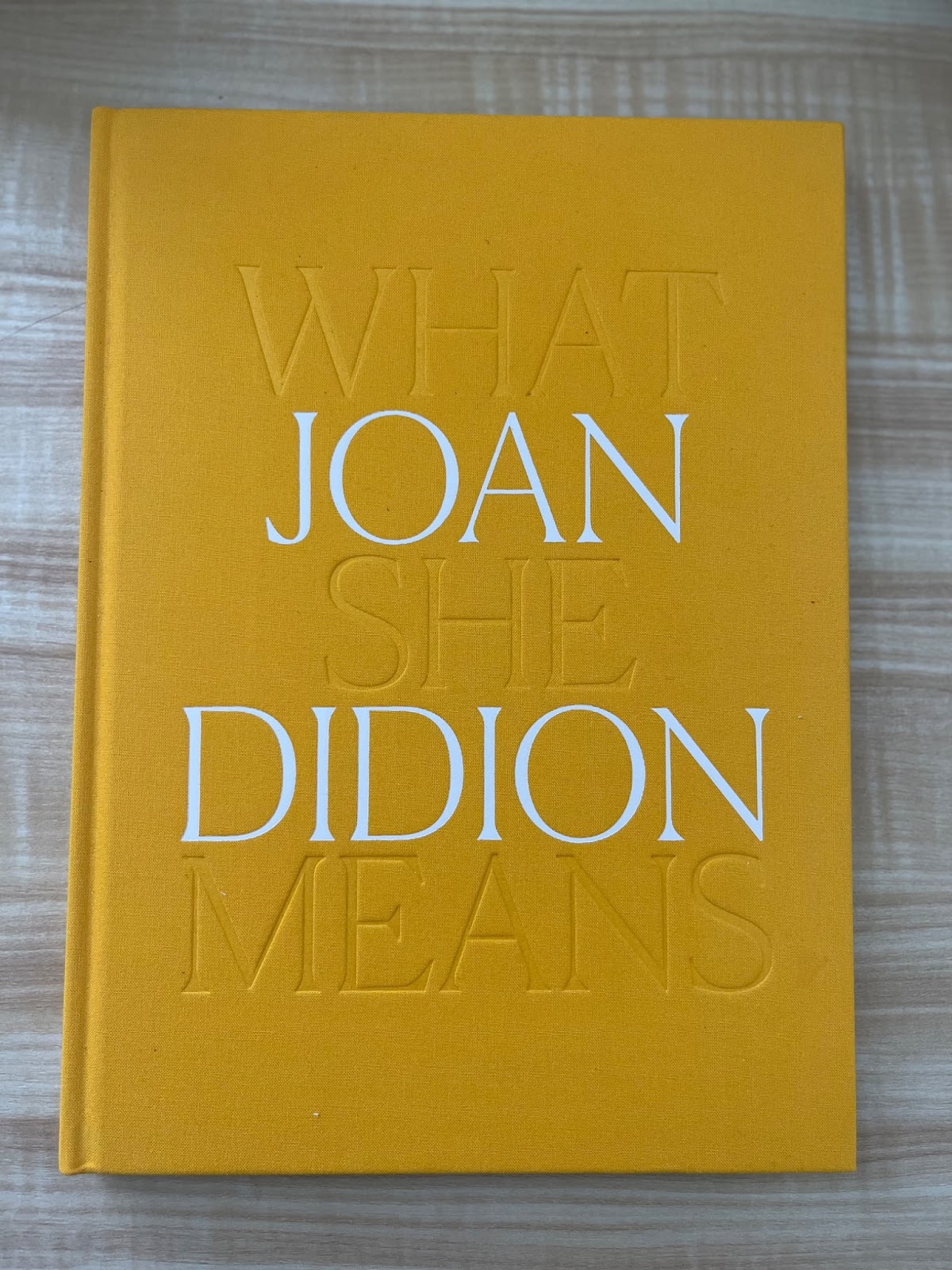

Joan Didion: What She Means, edited by Hilton Als, Connie Butler

I first read Didion in high school and didn’t “get” her—the cool detachment, the flatness, the existential drift that neared fatalism. It wasn't till I was 35, after I went back for my MFA, that I finally understood her voice—even felt a kinship. I purchased this coffee table book recently for textural inspiration both for my writing and work. It includes family heirlooms, yearbook photos, and curated art, and charts a visual journey through Joan’s life—from New York to Hollywood and Malibu and back.

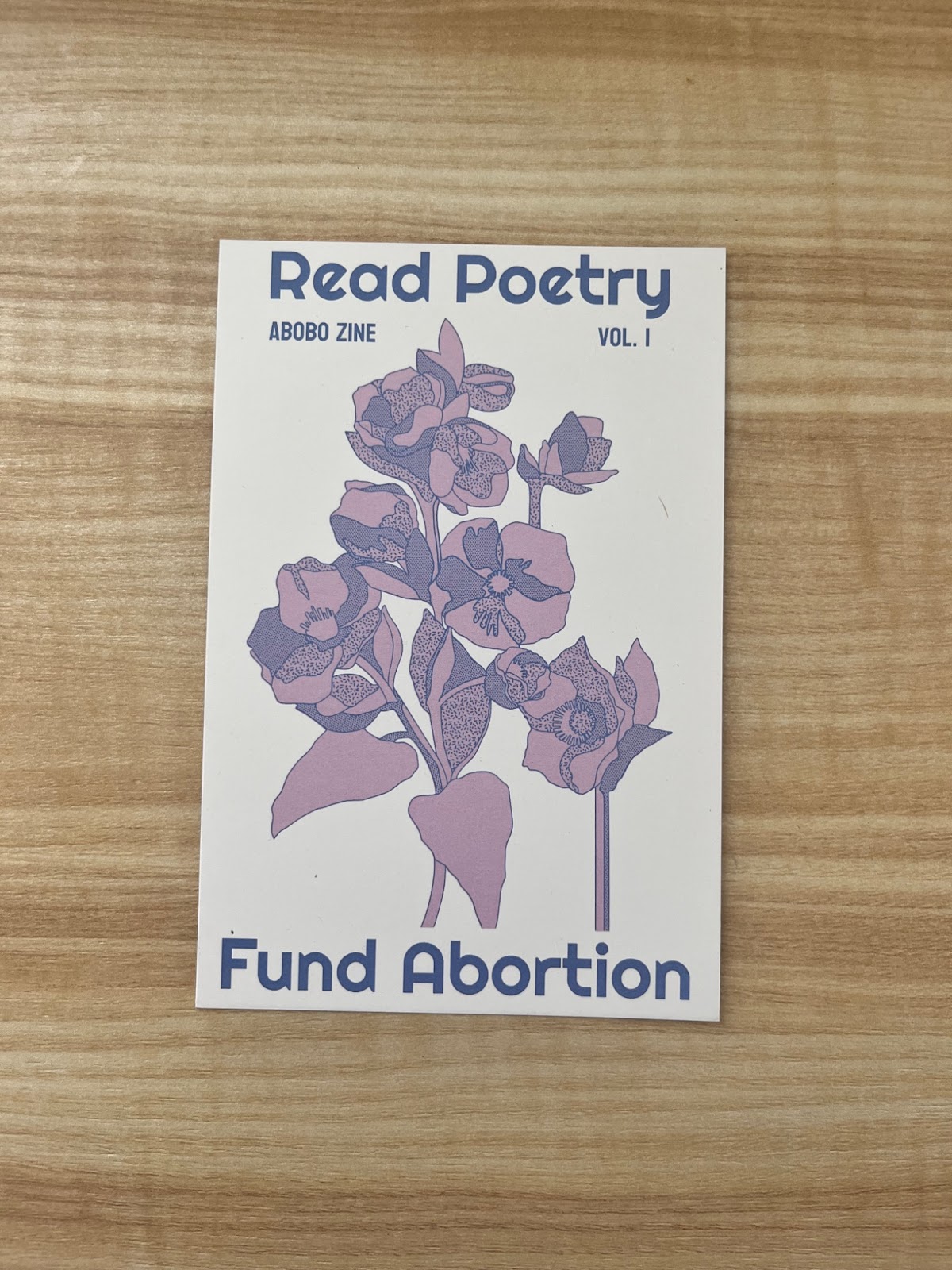

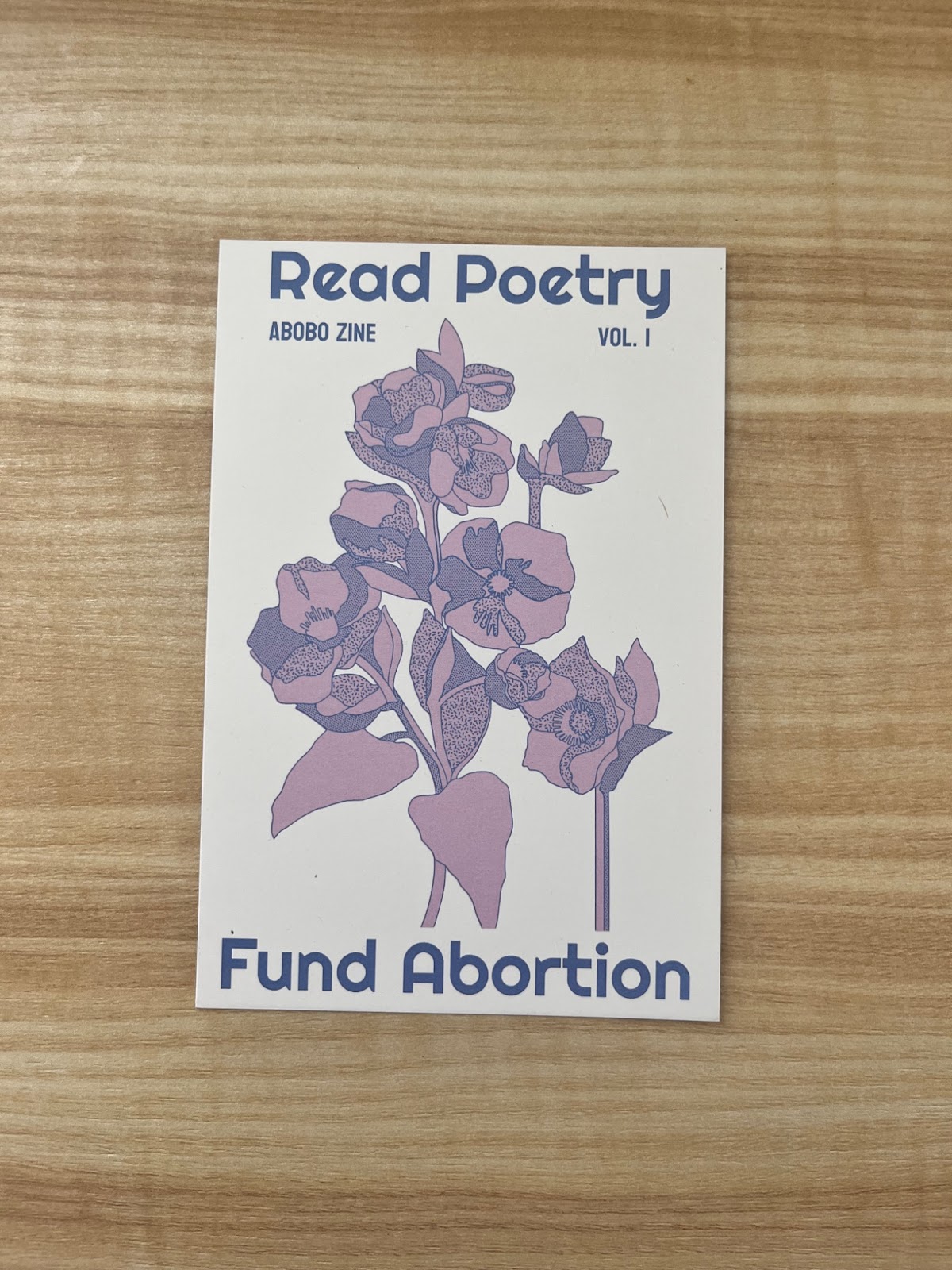

Read Poetry, Fund Abortion postcard

I had some poetry featured alongside the likes of Eileen Myles in Abobo Zine, which raises money for the National Network of Abortion Funds. These are two causes I care about deeply—and of course, zines: the photocopied, lo-fi pulse of punk culture swiftly stapled to say something of this moment, in this moment. This little piece of ephemera reminds me that poetry, like all writing, is political. Every poem is a series of choices—what to name, what to notice, what to speak to, what to leave unsaid.

Beats (of every kind)

Currently, I’m alternating between Spotify’s “Songs of Summer” playlist and “Italian Mobster Music.” My days, not surprisingly, feel very poolside margs-by-way-of-mortadella.

Heath Ceramics bud vase

For much of my career, I lived in the Bay and worked at agencies like Salt Branding and Character SF—just streets from the Ferry Building, where Heath, a Northern California-based tableware staple, had a tiny but tidy outpost. During a hard chapter of my life, when I was diagnosed with a stomach condition and struggled to eat, I often used my lunch break to wander that narrow stretch of building window-shopping. I bought this signature vase during that time, for that 20-something girl.

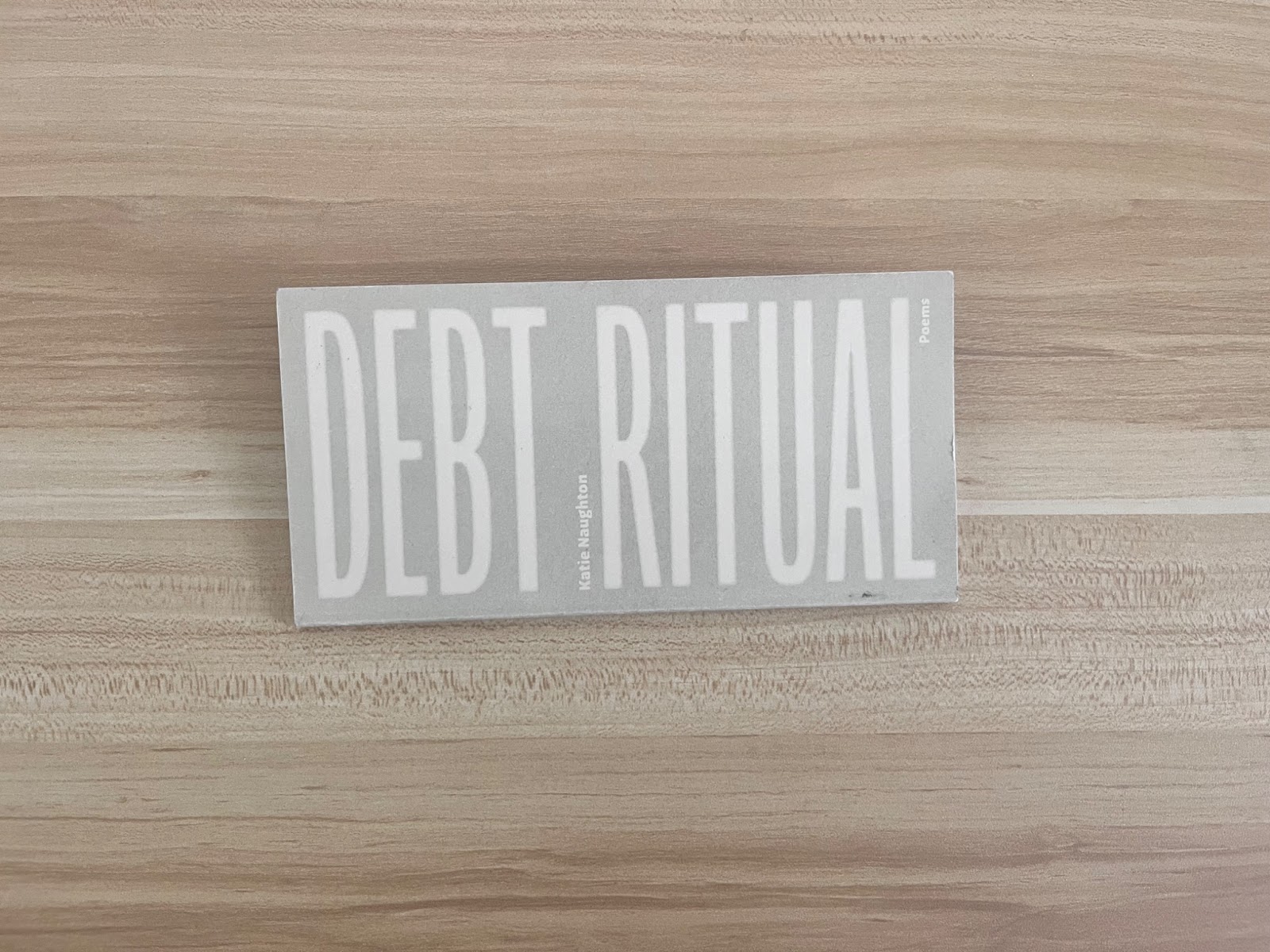

Debt Ritual, Katie Naughton

I recently saw Joan Didion’s Vogue resignation letter surfaced on LinkedIn, and one line in particular stuck with me: “I believe that I could offer… a great deal more if I could get around a little more. I feel at the moment very stale, which I thought for a while might be the way of the world but now think unnecessary." Several years ago, I too, traded in full-time work for freelance for that same freedom—to write and move…to the PNW, to the Florida Keys, to the thick of the South, and very soon to Costa Rica.

Katie Naughton’s Debt Ritual speaks to me in the same way Joan’s letter does. It asks: What have you given up for the illusion of security? What part of your voice has gotten left—even lost—in the Google Doc, Keynote, Excel Spreadsheet? What has the system convinced you is necessary that is in fact not?

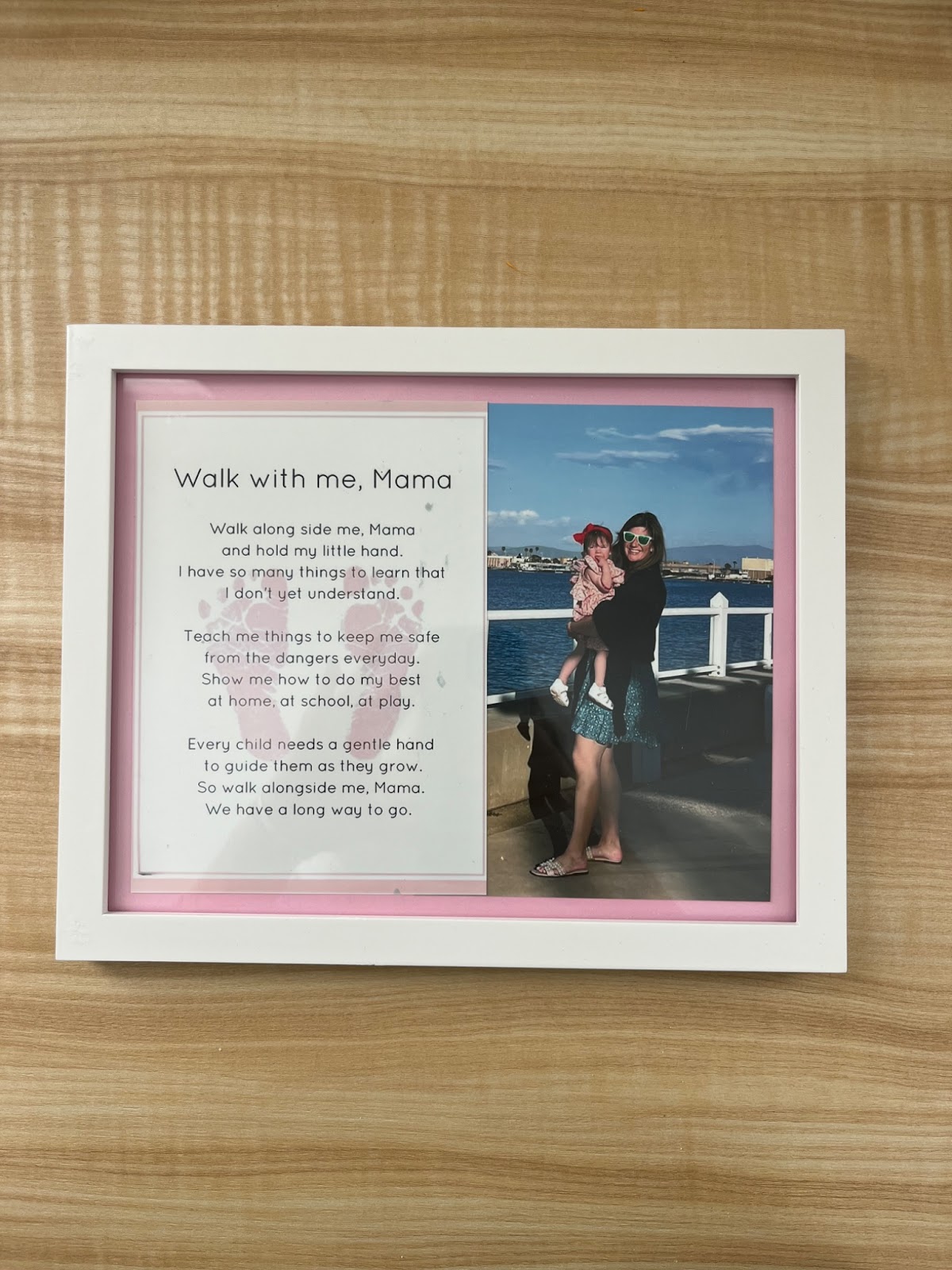

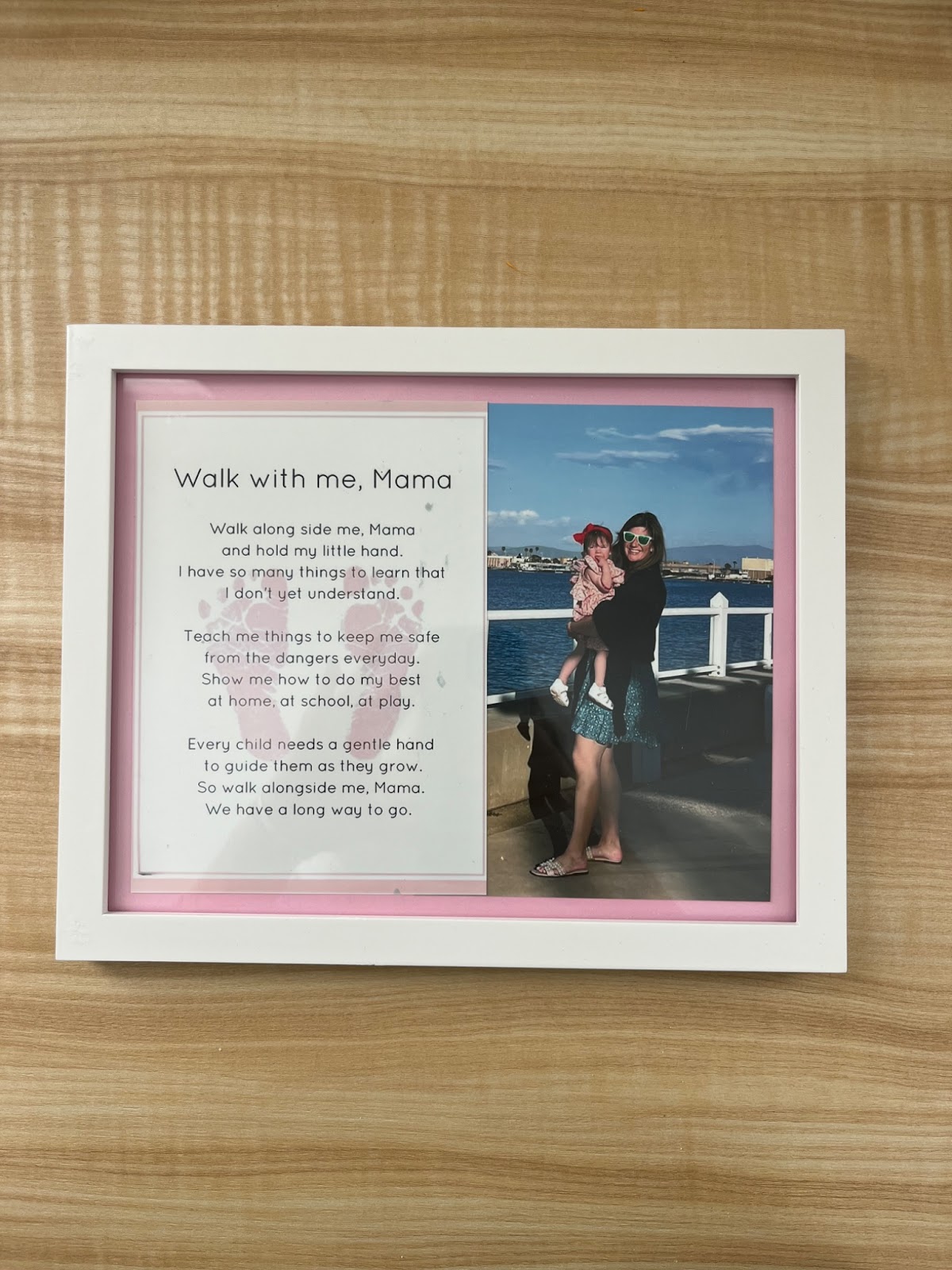

Walk With Me Mama poem, Photo

Nestled behind my laptop is a photo of me and my daughter on San Diego’s Coronado Island, and beside it, a short, sentimental poem gifted to me by my own mom. It sticks out. It’s too soft, saccharine, precious next to the rest of my desk: art books and poetry collections, postcards with real teeth. But maybe that’s the point. Because sentimentality has long been seen as unserious. Because mothers have long been viewed as too feely for the Zoom call. Too soft for the next level. Too motherly for upper management. And yet, motherhood hasn’t been reductive. It hasn’t made me—or the other mothers I know—less, but, instead, more. So much more.

Writing this, flanked by two windows, Betty looking down like some imperfect saint, I think about the imagined emergencies and Vogue videos, about what’s needed to make a living and what’s needed to live—how the most telling things sit beyond the Zoom window, are kept for no one but ourselves.

Stevie Belchak is a freelance namer, strategist, and writer living in Georgia. When she's not wording out for work, she's writing out of love—publishing poetry and essays in journals, across the web, and through her Substack, Mother Of.

I’ve had many desks—oaken and heavy, spare and intentional, cubicled and shared. They’ve stood in Soho, overlooked San Francisco’s Battery Street, and were perched in Oakland’s Tribune Tower. Once, I even sat with my back to the Potomac at The Watergate, turning now and then to catch the glint off the river’s blue. But only now, at 39 and five years into freelancing, do I finally have a desk that’s mine, and not just a surface to work on, but a site of real accumulation—a place to layer, collect, and make meaning. It’s where my commercial writer and poet selves sit across from each other, ideating over the same mug, scribbling in the same notebook, pulling from the same stack of books and postcards and prints.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about what gathers on a desk—and how ordinary objects become biographical. We all know words hold more than letters—they carry connotation, texture, tone, but so do the things we keep close. In semiotics—the study of signs, objects are never just functional. As Roland Barthes suggests, they’re loaded with private mythologies, cultural shorthand, and social residue.

Projects like The Burning House and Vogue’s The Bag get it: objects matter. The Burning House—a once-viral photo series that asked, “If your house were burning, what would you take?”—showcased items both curated and beloved: a stuffed squirrel, a roll of old film, an OP-1 synth, a passport. The Bag, on the other hand, trades in the real (or, at least, the aspirational), peeking inside celebrity totes to reveal Theragun minis, Laneige Lip Glowy Balm, gummy bears, and knitting needles. One is imagined, the other lived—but both reveal something deeper: how we make the intangible visible through what we choose to carry, display, and keep close. The bottom line is these snaps, still lifes, keepsakes—they tell our story.

That idea—that objects are not inert, but saturated with significance—has stayed with me. And it’s made me rethink my desk as a lens into the ways I work, who I am, and why.

So, what's on (and above) my desk? And, what do some of the objects say about me both as a freelancer—naming and strategizing and writing commercially—and as a writer's writer—writing and editing and publishing poems, essays, and more.

Betty Draper print

Back in my early 20s, I was studying brand strategy and copywriting at NYU while working in publishing—and Mad Men was the show. Then, Peggy, the lone female copywriter on Madison Avenue, was my north star. These days, as a mother with Rao’s pasta sauce in my hair and Google Calendar rage in my heart, I relate far more to the cigarette-wielding Betty. And in this particular print, Betty is eyeless and noseless, perfect. She’s also likely a stand-in for my long-running obsession with women in fragments, which probably began when I first saw Guy Bourdin’s Walking Legs, a Charles Jourdan campaign that starred disembodied mannequin limbs in heels. Back then, I found them eerie and oddly captivating. Now, they, like my Betty print, remind me of the mother I am: part, parceled, looked at but never fully seen.

Zirconia & Bad, Bad, Chelsea Minnis

Copywriters, take note: poet Chelsea Minnis is the queen of voice and a perfect reminder that the writer and the speaker are not the same thing. I turn to her when I need to slip into something more operatic—a feather boa of an “I,” all sequins, fur, and chaise lounges. In certain collections, her voice is really something to behold: over-the-top, glamorous, exaggerated, clichéd, and gloriously camp. And, yet, beneath the jewels, mink, and champagne flutes? There exists real truth.

HP DeskJet 2755e

I hadn’t touched a printer at home since I worked as an editorial assistant in NYC. After swearing off all glorified-secretary roles, I was certain I’d never need one again. Then came poetry, ready to prove me wrong. Now, as an editor with the press blush lit, I spend weekends printing out manuscripts and reviewing others’ collections. The rest of the time, I’m printing my own. This printer’s current job? Spitting out drafts and drafts alone. The below image showcases a poem from one of two manuscripts I am currently surfacing with presses, Full Bleed. And yes, the printer drinks ink like a fiend.

The Revolutionary Letters, Diane Di Prima

Some people have burn books. Some people have little black books. Other people have tiny red books—specifically this one. BEAT poet Diane di Prima first published this tiny pocket of poetic resistance with SF's City Lights Books in 1971.

Don’t read if you’d rather not critically interrogate your role as a knowledge worker in late capitalism.

Do read if you're ready to rethink the brands you write (and name) for, the clients you valorize, and the ways in which you show up in the world.

The Nondescript Bird

Chekhov has his guns, and we poets and namers have our birds: Twitter, Hootsuite, Nest, Thunderbird, Golden Goose, Bluebird Bio, Albatross Designs, Redhawk Wealth Advisors.

Need I say more.

Notebook (unknown origin, aquamarine)

I find I do my best writing in the morning, and following a Maker's Schedule, I like to keep my 9 AM - 1 PM EST blocked. But when it comes to naming? My best work happens somewhere between dreaming and the not-quite-awake state. It’s known that sleep helps us organize ideas and make sense of our days, but it’s that moment before or after total darkness—the slippery in-between—where magic happens for me. My little lined notebook goes to bed with me every night and shows up to work with me every morning, usually peppered with name ideas, looping thoughts, and rabid iterations.

Pentax ME Super

I bought this used Pentax ME Super a few years ago because the places I’ve lived have always felt generative. From photographing container ships along the Columbus River and the sky purpling behind them to capturing the sea edged in by palm fronds in the Keys, I started a kind of visual journal of my life. With time, though, I began seeking out not just documentation but Barthes’ punctum—that thing which wounds, pierces, stings. The absurd. The uncanny. The ironic. A toy Pumba lodged in a cement pole, a half-submerged candy cane in a resort pool, birds gathered at a gas station—one performing a monologue from a telephone line. That's when photography turned for me, and I saw it as a way to express irony, cynicism, and dystopic feelings through the world I alone framed. And, the walks I take? They’ve proven essential for my writing and thinking and ideating, my meaning making.

Joan Didion: What She Means, edited by Hilton Als, Connie Butler

I first read Didion in high school and didn’t “get” her—the cool detachment, the flatness, the existential drift that neared fatalism. It wasn't till I was 35, after I went back for my MFA, that I finally understood her voice—even felt a kinship. I purchased this coffee table book recently for textural inspiration both for my writing and work. It includes family heirlooms, yearbook photos, and curated art, and charts a visual journey through Joan’s life—from New York to Hollywood and Malibu and back.

Read Poetry, Fund Abortion postcard

I had some poetry featured alongside the likes of Eileen Myles in Abobo Zine, which raises money for the National Network of Abortion Funds. These are two causes I care about deeply—and of course, zines: the photocopied, lo-fi pulse of punk culture swiftly stapled to say something of this moment, in this moment. This little piece of ephemera reminds me that poetry, like all writing, is political. Every poem is a series of choices—what to name, what to notice, what to speak to, what to leave unsaid.

Beats (of every kind)

Currently, I’m alternating between Spotify’s “Songs of Summer” playlist and “Italian Mobster Music.” My days, not surprisingly, feel very poolside margs-by-way-of-mortadella.

Heath Ceramics bud vase

For much of my career, I lived in the Bay and worked at agencies like Salt Branding and Character SF—just streets from the Ferry Building, where Heath, a Northern California-based tableware staple, had a tiny but tidy outpost. During a hard chapter of my life, when I was diagnosed with a stomach condition and struggled to eat, I often used my lunch break to wander that narrow stretch of building window-shopping. I bought this signature vase during that time, for that 20-something girl.

Debt Ritual, Katie Naughton

I recently saw Joan Didion’s Vogue resignation letter surfaced on LinkedIn, and one line in particular stuck with me: “I believe that I could offer… a great deal more if I could get around a little more. I feel at the moment very stale, which I thought for a while might be the way of the world but now think unnecessary." Several years ago, I too, traded in full-time work for freelance for that same freedom—to write and move…to the PNW, to the Florida Keys, to the thick of the South, and very soon to Costa Rica.

Katie Naughton’s Debt Ritual speaks to me in the same way Joan’s letter does. It asks: What have you given up for the illusion of security? What part of your voice has gotten left—even lost—in the Google Doc, Keynote, Excel Spreadsheet? What has the system convinced you is necessary that is in fact not?

Walk With Me Mama poem, Photo

Nestled behind my laptop is a photo of me and my daughter on San Diego’s Coronado Island, and beside it, a short, sentimental poem gifted to me by my own mom. It sticks out. It’s too soft, saccharine, precious next to the rest of my desk: art books and poetry collections, postcards with real teeth. But maybe that’s the point. Because sentimentality has long been seen as unserious. Because mothers have long been viewed as too feely for the Zoom call. Too soft for the next level. Too motherly for upper management. And yet, motherhood hasn’t been reductive. It hasn’t made me—or the other mothers I know—less, but, instead, more. So much more.

Writing this, flanked by two windows, Betty looking down like some imperfect saint, I think about the imagined emergencies and Vogue videos, about what’s needed to make a living and what’s needed to live—how the most telling things sit beyond the Zoom window, are kept for no one but ourselves.

Stevie Belchak is a freelance namer, strategist, and writer living in Georgia. When she's not wording out for work, she's writing out of love—publishing poetry and essays in journals, across the web, and through her Substack, Mother Of.

.jpeg)