Brands haven’t always blindly amplified rigid ideas about gender. In moments when progressive ideas about gender gained cultural momentum, some brands responded by aligning themselves with a more progressive worldview.

At times, it felt like progress had become a desirable brand value in itself. Gender representation in branding appeared to be moving steadily toward inclusivity and diversity. What used to be a fringe position was seen as the modern way of representing the world.

In this second installment of Gender and Brand, I explore how brands have navigated the tension between genuine progress and representation that looks progressive without challenging existing systems. I focus on three major themes— pushing for a more inclusive beauty standard, directly subverting gender roles, and how feminist branding efforts have been integrated into industry norms. These shifts show how far brands have come, but how difficult it remains for many to fully detach from underlying assumptions about gender and value.

A Widening Definition of Beauty

In the 2010s, advertisements began representing women in a more down-to-earth, stripped-down way that expanded what counted as beauty. These campaigns reframed women as existing outside of the roles of housewife or muse, representing them as individuals with their own social value.

Dove’s Real Beauty campaign widened the scope of beauty by portraying “real women” or women who fell outside the ultra-thin, often white or light-skinned, airbrushed images long celebrated in advertising. Un-retouched photos, average body types, and slightly improved racial and age diversity felt like a reset after decades of curated images of supermodel-esque women. These ads asserted that a unique form of beauty existed in every woman, and all women should be celebrated for their beauty.

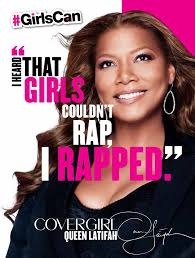

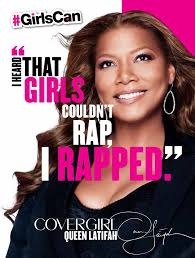

The CoverGirl #GirlsCan campaign similarly framed empowerment as the alternative to cultural misogyny. These ads featured well-known women in powerful poses, speaking about their experience overcoming gender-based stereotypes. The campaign’s slogan “#GirlsCan look good and feel good” wraps this idea of empowerment into the beauty umbrella.

Widening the definition of beauty is not the same as questioning why women must cultivate beauty to maintain social value. Instead, Dove and CoverGirl pushed the envelope only slightly, working within a comfortable structure that assumes women must be beautiful to be valuable. This strategy allowed these brands to both embody a progressive tone and not push so hard that it would hurt their bottom line.

The 2010s were one of the most notable eras for empowerment-centered ads, but brands have historically capitalized on the social wins of women to appeal to them.

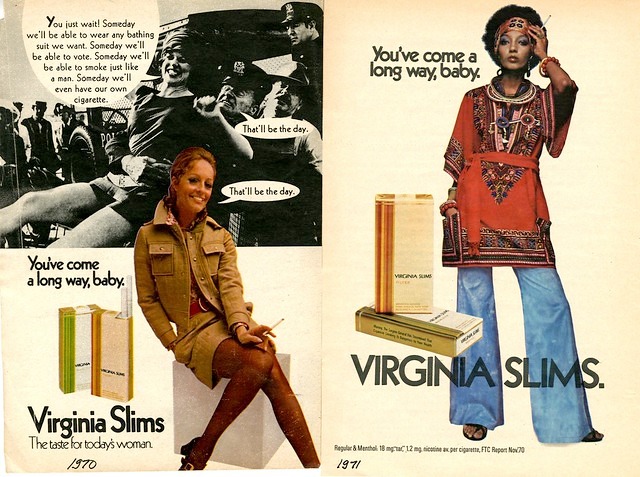

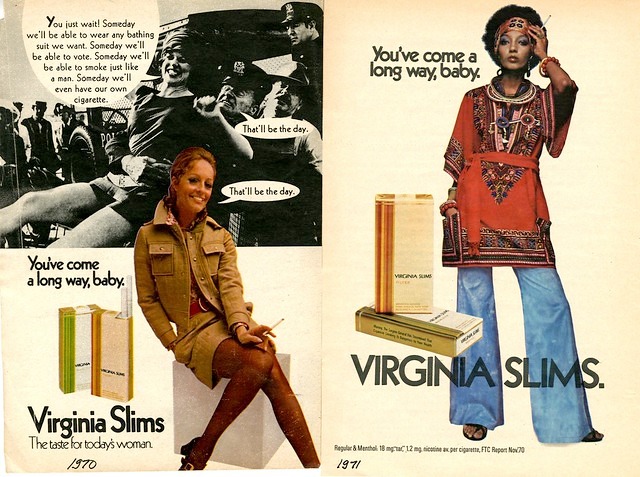

A 70s Virginia Slims ad contrasts an image of a woman being arrested for violating public dress code in the 1950s with one of a cigarette-smoking, modern woman. The ad celebrates how far women have come, but what are they really celebrating? Liberation doesn't mean earning the right to look cool while selling a product.

Subverting the Standard

By the early 2020s, empowerment-centered branding started feeling overplayed and cultural attitudes about beauty had shifted. Expanding the category of beauty started feeling more shallow than progressive, and many people began viewing the idea of over-investing in chasing beauty to be a harmful focus in itself.

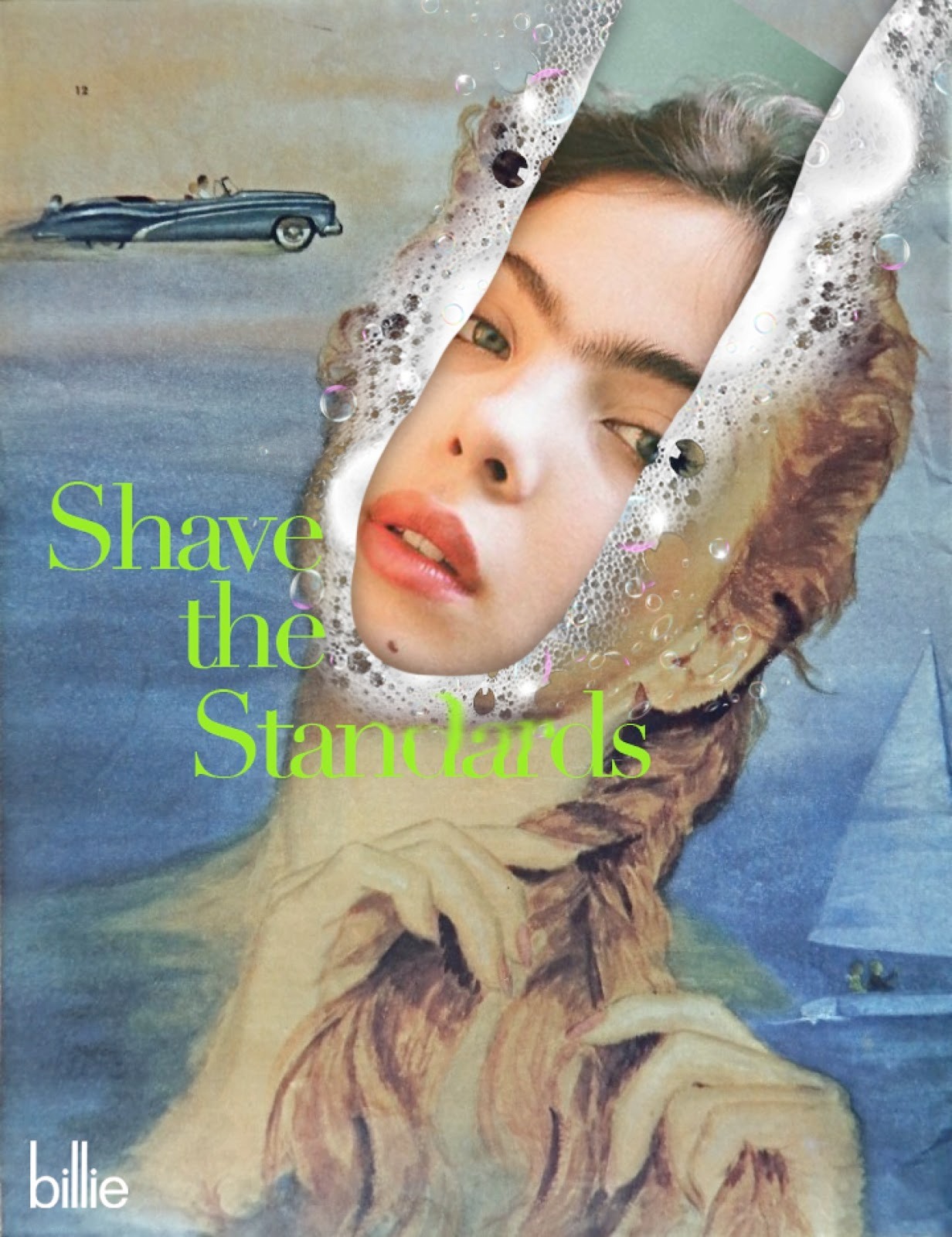

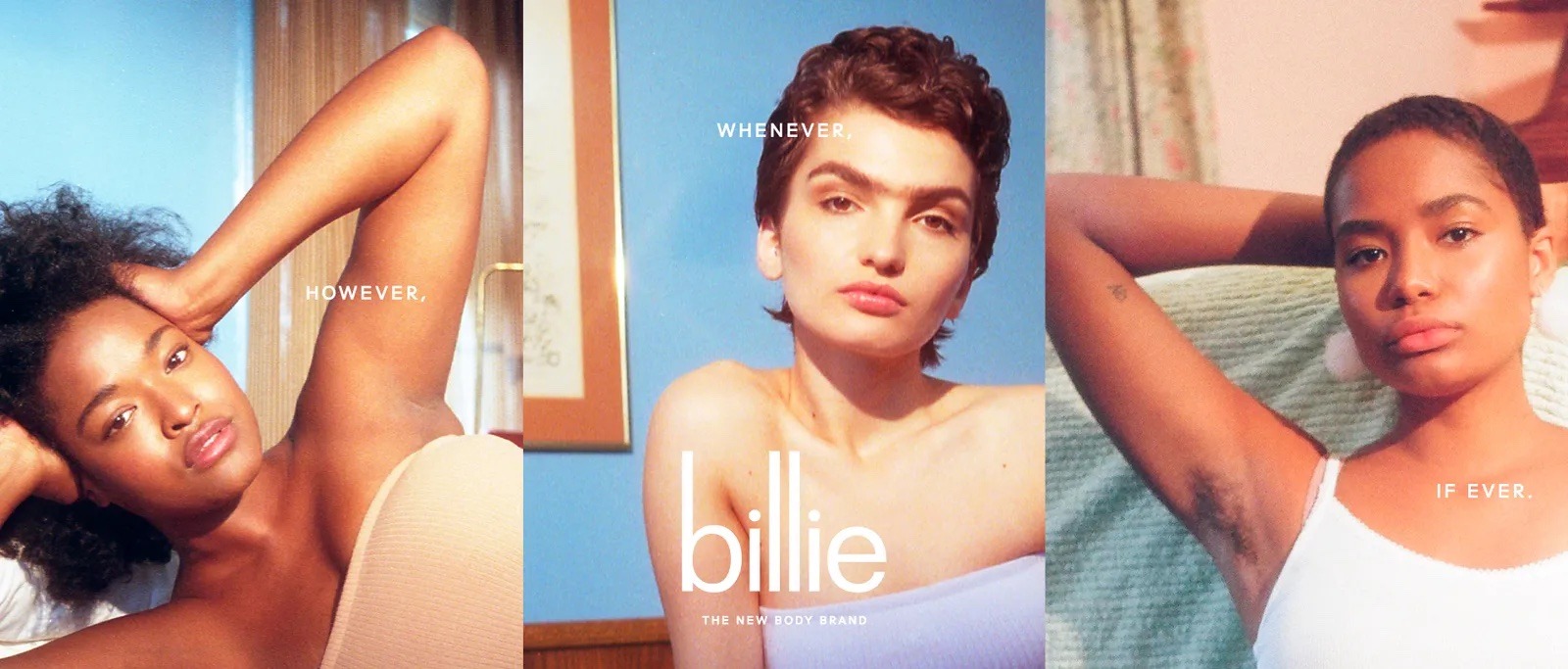

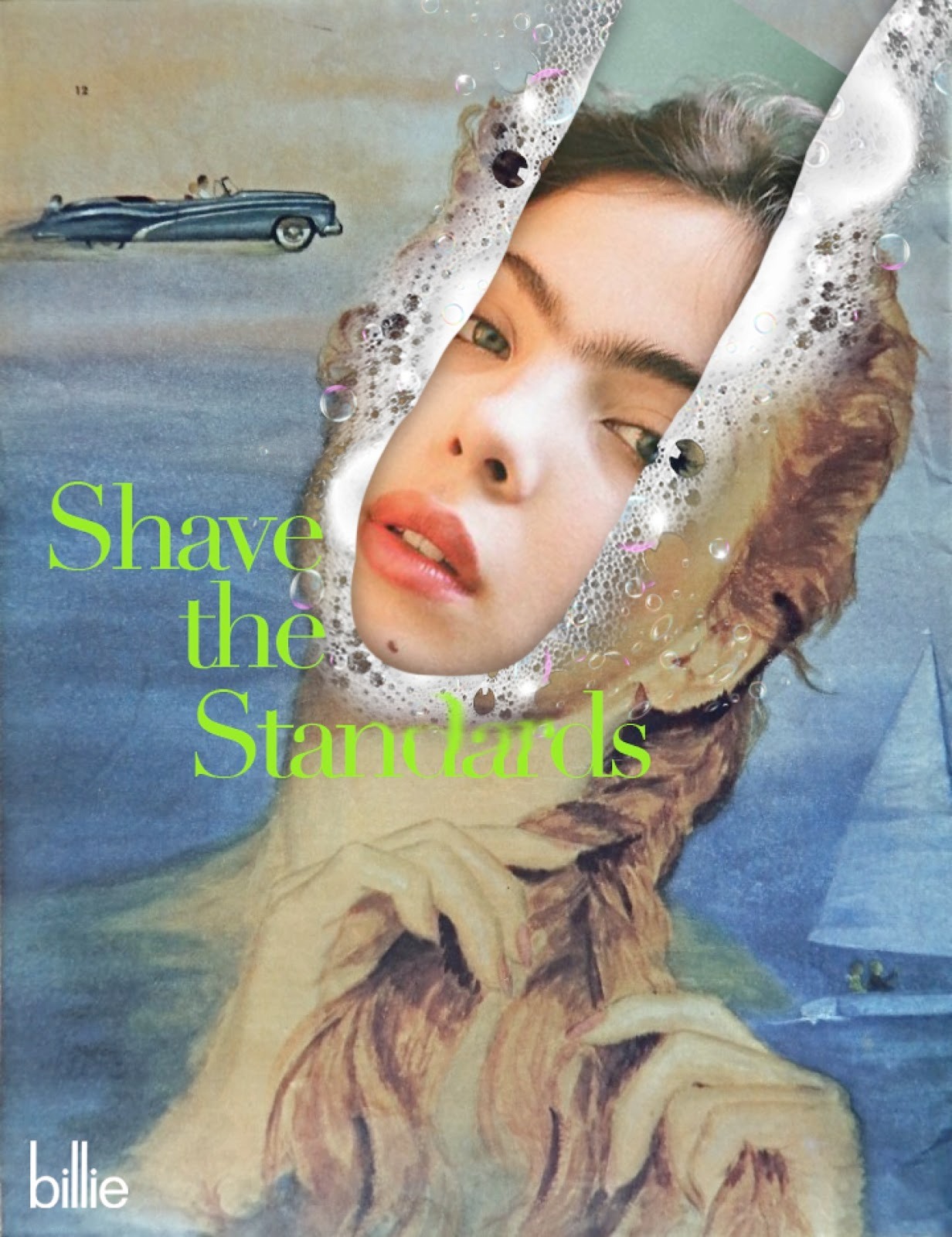

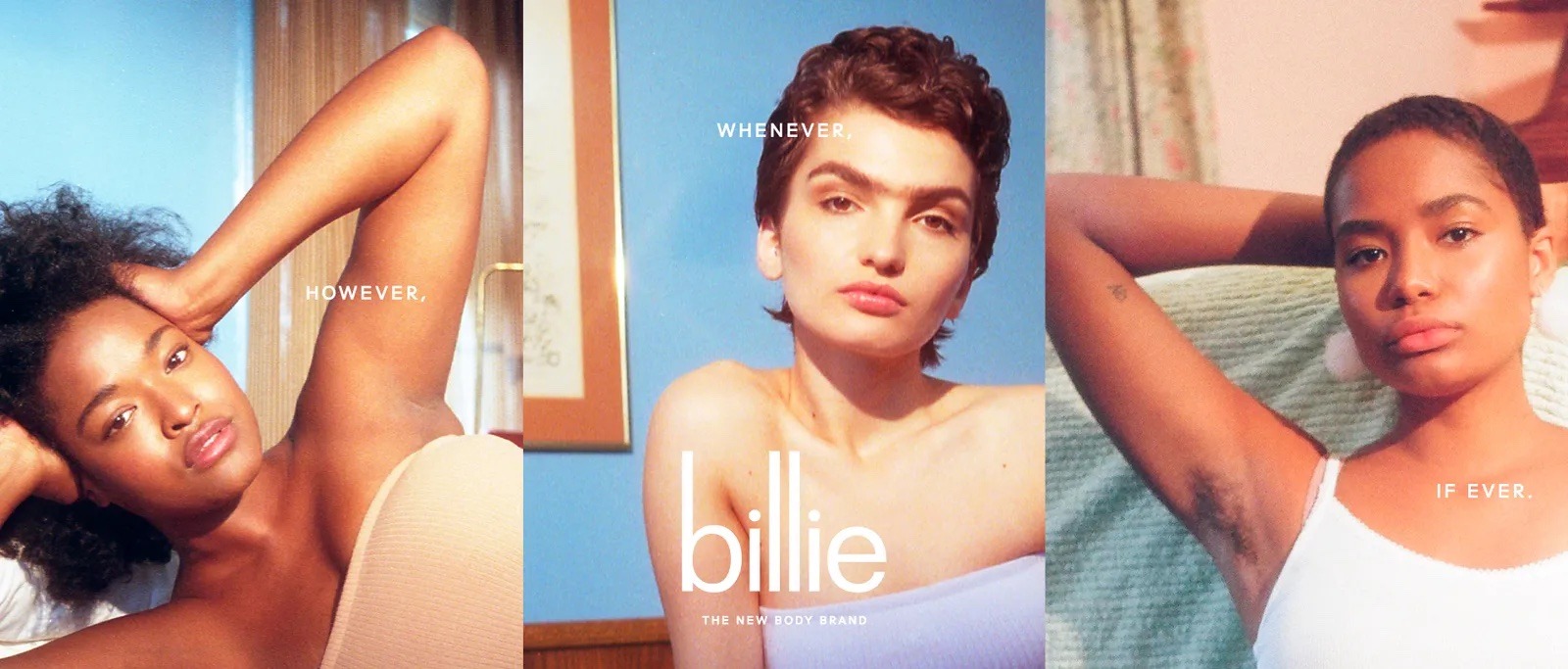

A new branding strategy emerged that championed subtlety as a means to signal neutrality and utility over overt messaging about beauty. The razor and shaving company Billie emerged with a pastel, muted aesthetic that positioned their products in a more feminine- leaning, but ultimately gender-neutral visual space. In its brand storytelling, Billie emphasizes that shaving is an optional task, and is ambiguous about the gender of their target audience. While most of the people presented in their ads are women or feminine-presenting, many defy grooming norms.

The line, “You don’t need to shave, but we’re here for when you want to” offers a supportive, low-pressure alternative to the promise that every woman can fit the beauty standard if the standard is just a bit more forgiving. Instead, Billie acknowledges that beauty norms exist, and positions itself as a brand for people who choose to participate in them—whether it’s partially or fully.

Billie positions shaving as a choice, which challenges the assumption that all women must choose to shave and all must choose to shave the same way. Although it’s an improved notion, the choice to participate doesn’t free women from being held to the beauty standard or facing social rewards or consequences for their choices.

No matter how the branding is spun, Billie ultimately benefits from the deeply ingrained idea that women need to shave. Without this expectation, Billie wouldn’t need to exist either. The brand’s nontraditional messaging, diverse representation, and deviation from overtly feminine branding are all in opposition to the ideology that led up to their existence as a brand.

Despite this contradiction, Billie comes close to a feminist representation of shaving. One could even argue that the brand’s own messaging hurts its profitability in favor of promoting a progressive view of body hair. Even when challenging standards, Billie can’t operate outside of the market that depends on these standards to exist. Billie demonstrates how despite the strides gender representation has made, there are limits to how much branding alone can affect social change.

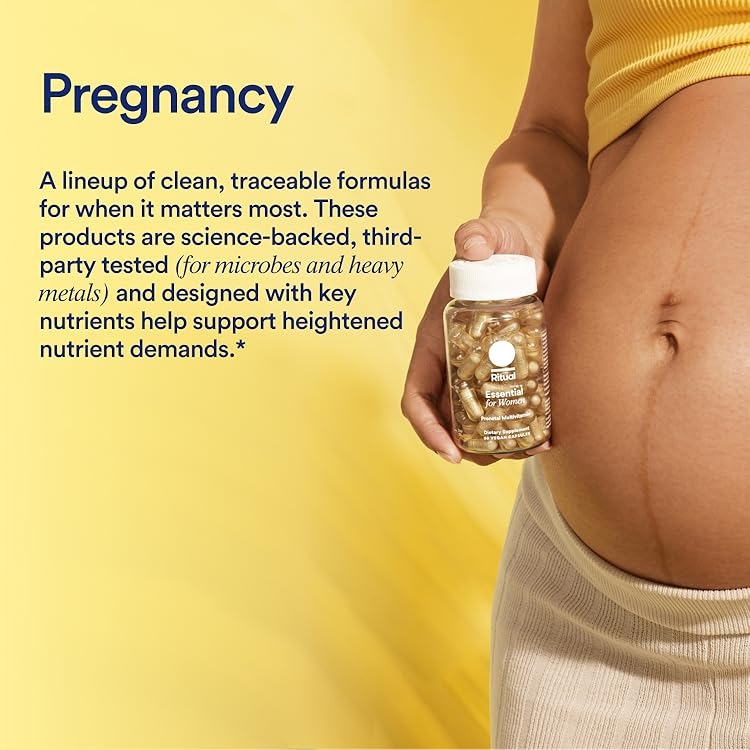

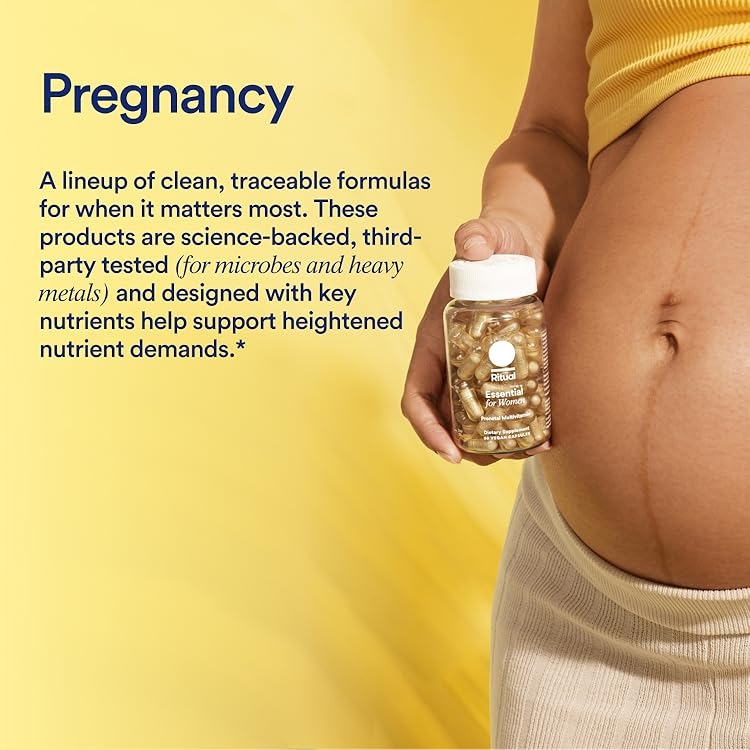

Ritual utilizes a similar minimalistic, neutral approach. Their emphasis on ingredients and function diverts from traditional feminine cues, an especially revolutionary positioning for pregnancy-related supplements. The line “for the real body builders” celebrates the resilience and strength required for pregnancy, without unnecessary fluff. This representation allows women and other pregnant people to feel represented for their strength.

Ritual chooses to tell the story of pregnancy as something existing outside of a beauty standard or the start of a restrictive view of motherhood. The ad regards pregnancy as it relates to the person who is actually pregnant and what they need to support their body going through it. It’s not a story about what that means for her identity once she gives birth.

This branding doesn’t speak out against a specific standard, but embodies strength without explicitly announcing diversion from any standard.

Industry Recognition

As progressive portrayals of gender and marginalized groups continued to pick up in the 2010s, Cannes introduced the Glass Lion award in 2015 to amplify campaigns that celebrated social progress for marginalized groups. The creation of this award showed an institutional-level shift toward valuing authentic representation rather than amplifying stereotypes.

An award like this shows that industry values have meaningfully shifted since the golden age of advertising, when accurate portrayals were rarely prioritized over appealing to consumers through the narratives they were comfortable with. While the Glass Lion does not guarantee that all brands will choose to value representing marginalized groups, it does make a cultural statement that progressive representation is valued in the advertising industry.

Even with progress we’ve examined, the original gendered advertising script has stuck around. The system of patriarchy is so deeply entrenched that regressing can feel much easier than the ongoing work of cultivating inclusive representation. Recent examples show how quickly brands have adopted aesthetics of progressive gender representation, and how quickly they abandon them when the cultural attitude shifts. In the next installment, I’ll explore why some brands continue to rely on regressive ideas about gender, despite the industry-wide effort toward evolving from the past.

Izzy Colón is a culture writer, creative copywriter, and Contributing Writer for The Subtext. She lives in Chicago, where she spends as much time collecting stories as she does writing them.

Brands haven’t always blindly amplified rigid ideas about gender. In moments when progressive ideas about gender gained cultural momentum, some brands responded by aligning themselves with a more progressive worldview.

At times, it felt like progress had become a desirable brand value in itself. Gender representation in branding appeared to be moving steadily toward inclusivity and diversity. What used to be a fringe position was seen as the modern way of representing the world.

In this second installment of Gender and Brand, I explore how brands have navigated the tension between genuine progress and representation that looks progressive without challenging existing systems. I focus on three major themes— pushing for a more inclusive beauty standard, directly subverting gender roles, and how feminist branding efforts have been integrated into industry norms. These shifts show how far brands have come, but how difficult it remains for many to fully detach from underlying assumptions about gender and value.

A Widening Definition of Beauty

In the 2010s, advertisements began representing women in a more down-to-earth, stripped-down way that expanded what counted as beauty. These campaigns reframed women as existing outside of the roles of housewife or muse, representing them as individuals with their own social value.

Dove’s Real Beauty campaign widened the scope of beauty by portraying “real women” or women who fell outside the ultra-thin, often white or light-skinned, airbrushed images long celebrated in advertising. Un-retouched photos, average body types, and slightly improved racial and age diversity felt like a reset after decades of curated images of supermodel-esque women. These ads asserted that a unique form of beauty existed in every woman, and all women should be celebrated for their beauty.

The CoverGirl #GirlsCan campaign similarly framed empowerment as the alternative to cultural misogyny. These ads featured well-known women in powerful poses, speaking about their experience overcoming gender-based stereotypes. The campaign’s slogan “#GirlsCan look good and feel good” wraps this idea of empowerment into the beauty umbrella.

Widening the definition of beauty is not the same as questioning why women must cultivate beauty to maintain social value. Instead, Dove and CoverGirl pushed the envelope only slightly, working within a comfortable structure that assumes women must be beautiful to be valuable. This strategy allowed these brands to both embody a progressive tone and not push so hard that it would hurt their bottom line.

The 2010s were one of the most notable eras for empowerment-centered ads, but brands have historically capitalized on the social wins of women to appeal to them.

A 70s Virginia Slims ad contrasts an image of a woman being arrested for violating public dress code in the 1950s with one of a cigarette-smoking, modern woman. The ad celebrates how far women have come, but what are they really celebrating? Liberation doesn't mean earning the right to look cool while selling a product.

Subverting the Standard

By the early 2020s, empowerment-centered branding started feeling overplayed and cultural attitudes about beauty had shifted. Expanding the category of beauty started feeling more shallow than progressive, and many people began viewing the idea of over-investing in chasing beauty to be a harmful focus in itself.

A new branding strategy emerged that championed subtlety as a means to signal neutrality and utility over overt messaging about beauty. The razor and shaving company Billie emerged with a pastel, muted aesthetic that positioned their products in a more feminine- leaning, but ultimately gender-neutral visual space. In its brand storytelling, Billie emphasizes that shaving is an optional task, and is ambiguous about the gender of their target audience. While most of the people presented in their ads are women or feminine-presenting, many defy grooming norms.

The line, “You don’t need to shave, but we’re here for when you want to” offers a supportive, low-pressure alternative to the promise that every woman can fit the beauty standard if the standard is just a bit more forgiving. Instead, Billie acknowledges that beauty norms exist, and positions itself as a brand for people who choose to participate in them—whether it’s partially or fully.

Billie positions shaving as a choice, which challenges the assumption that all women must choose to shave and all must choose to shave the same way. Although it’s an improved notion, the choice to participate doesn’t free women from being held to the beauty standard or facing social rewards or consequences for their choices.

No matter how the branding is spun, Billie ultimately benefits from the deeply ingrained idea that women need to shave. Without this expectation, Billie wouldn’t need to exist either. The brand’s nontraditional messaging, diverse representation, and deviation from overtly feminine branding are all in opposition to the ideology that led up to their existence as a brand.

Despite this contradiction, Billie comes close to a feminist representation of shaving. One could even argue that the brand’s own messaging hurts its profitability in favor of promoting a progressive view of body hair. Even when challenging standards, Billie can’t operate outside of the market that depends on these standards to exist. Billie demonstrates how despite the strides gender representation has made, there are limits to how much branding alone can affect social change.

Ritual utilizes a similar minimalistic, neutral approach. Their emphasis on ingredients and function diverts from traditional feminine cues, an especially revolutionary positioning for pregnancy-related supplements. The line “for the real body builders” celebrates the resilience and strength required for pregnancy, without unnecessary fluff. This representation allows women and other pregnant people to feel represented for their strength.

Ritual chooses to tell the story of pregnancy as something existing outside of a beauty standard or the start of a restrictive view of motherhood. The ad regards pregnancy as it relates to the person who is actually pregnant and what they need to support their body going through it. It’s not a story about what that means for her identity once she gives birth.

This branding doesn’t speak out against a specific standard, but embodies strength without explicitly announcing diversion from any standard.

Industry Recognition

As progressive portrayals of gender and marginalized groups continued to pick up in the 2010s, Cannes introduced the Glass Lion award in 2015 to amplify campaigns that celebrated social progress for marginalized groups. The creation of this award showed an institutional-level shift toward valuing authentic representation rather than amplifying stereotypes.

An award like this shows that industry values have meaningfully shifted since the golden age of advertising, when accurate portrayals were rarely prioritized over appealing to consumers through the narratives they were comfortable with. While the Glass Lion does not guarantee that all brands will choose to value representing marginalized groups, it does make a cultural statement that progressive representation is valued in the advertising industry.

Even with progress we’ve examined, the original gendered advertising script has stuck around. The system of patriarchy is so deeply entrenched that regressing can feel much easier than the ongoing work of cultivating inclusive representation. Recent examples show how quickly brands have adopted aesthetics of progressive gender representation, and how quickly they abandon them when the cultural attitude shifts. In the next installment, I’ll explore why some brands continue to rely on regressive ideas about gender, despite the industry-wide effort toward evolving from the past.

Izzy Colón is a culture writer, creative copywriter, and Contributing Writer for The Subtext. She lives in Chicago, where she spends as much time collecting stories as she does writing them.

.avif)