As commercial writers, we lean on what we know—familiar phrases, recycled metaphors, industry clichés, because they’re efficient. And today’s AI tools, trained on vast corpora of human language, don’t just echo these habits but reinforce them, keeping us in what can feel like an infinite loop.

Poetry, however, asks for the opposite.

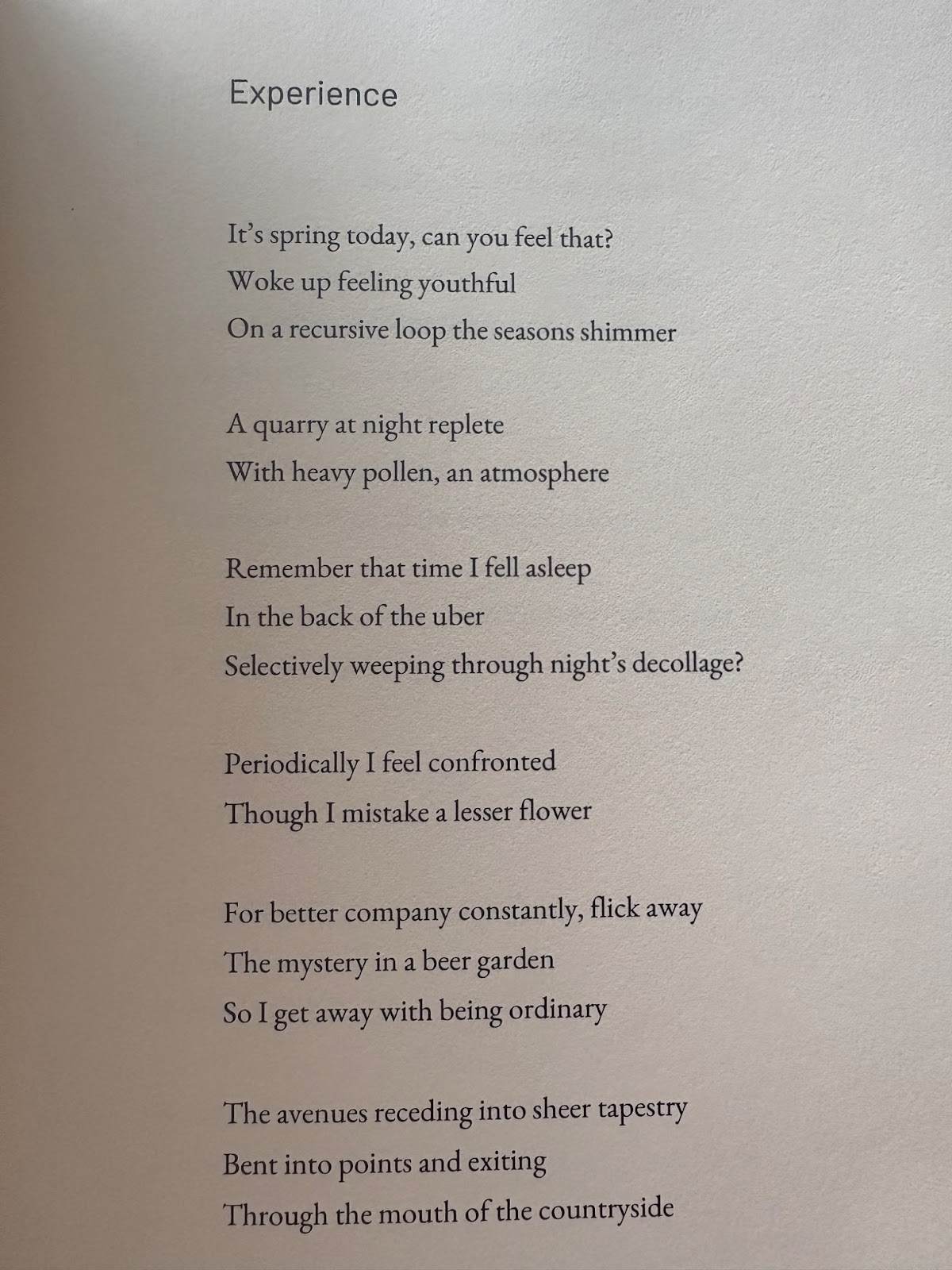

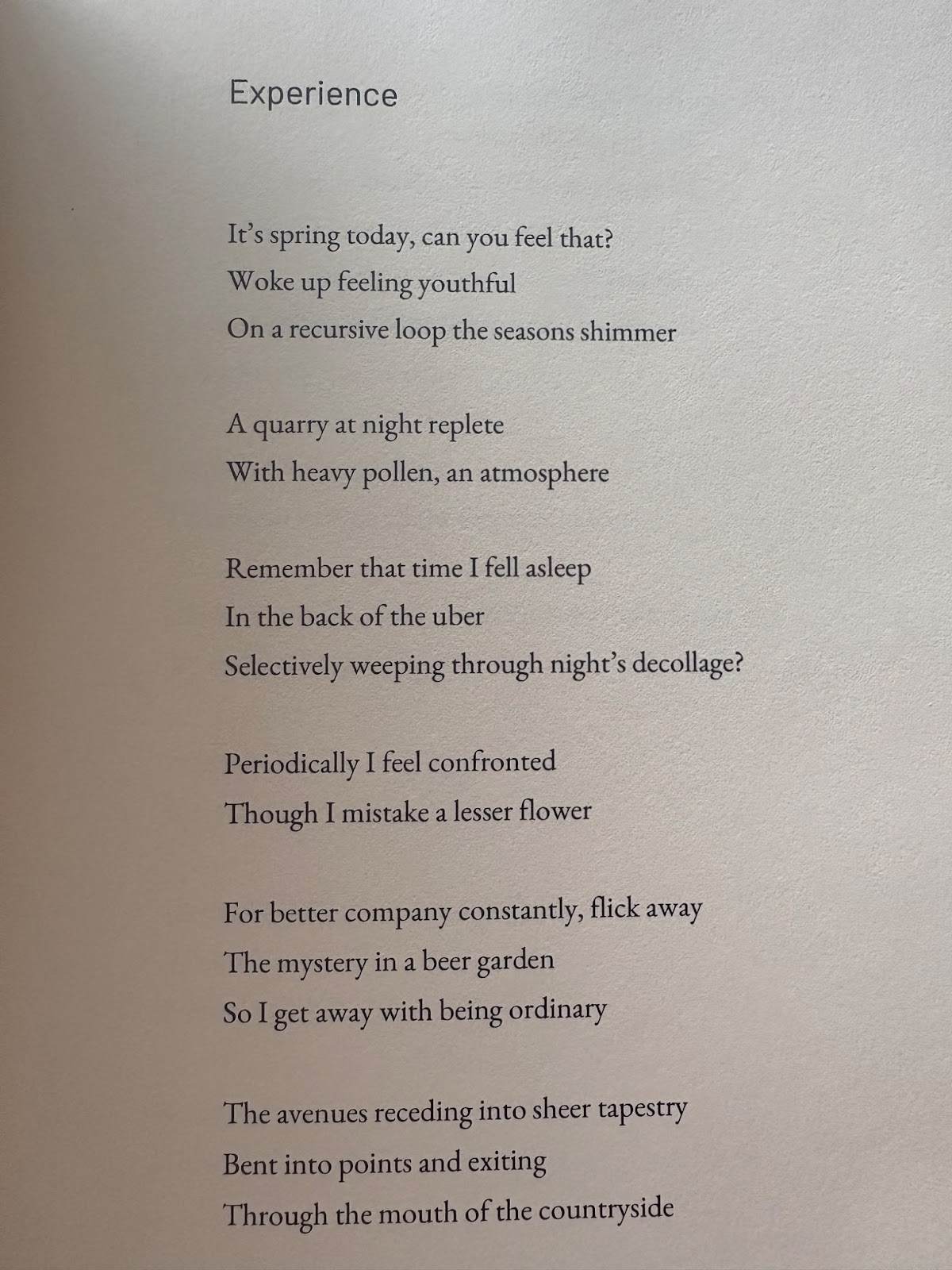

Poetry invites us to break the line. It asks us to collide nouns and modifiers into happy accidents that sing. It asks us to create imagery that feels impossible and new–think: Hunter Larson’s “mouth of the countryside” (pictured below) or Cynthia Cruz’s “mink / Lined winter.” It asks us to pause, to examine, to make the ordinary strange. To write a window, then open it, and step outside.

This month I had the pleasure of teaching How to Build Your Writing Muscle Through Poetic Practice. The group that Zoomed in was made up of copywriters, brand storytellers, marketers, and journalists—people who, like me, spend their days inside voice and tone guidelines and client constraints. Together we lifted out of words’ well-worn grooves, to see what else language could do. Specifically, we took a page out of poetry’s book to understand language’s infinite possibilities.

These were the lessons shared, the ones we can borrow as commercial writers. Some might call them small apertures into a new way of doing what we love, others: Miracle-Gro for our writerly minds.

Lesson 1: Slow Down

In our professional roles, we’re trained to critique, fix, resolve—and above all, to “get to the point.” But poetry reminds us that meaning often emerges not from efficiency but from slowing down.

The French philosopher Simone Weil once said, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” Much of poetry embodies that generosity—it lingers on the ordinary, noticing what might otherwise pass unseen.

One of James Schuyler’s famed Payne Whitney poems is a poem that does just that. What’s striking about “Sleep” is that the speaker doesn’t appear until the final line (“Give my love to, oh, anybody”). What precedes it is a poem gathered in fragments and one of pure description. There are tangerines, a doily, a pierced ear, an overheard conversation, heart-shaped cookies, a crescent moon. Nothing is extraordinary, and yet, through the attention given to each detail, each detail becomes exceptional, luminous. In this way, the poem suggests that perception itself—patient, unhurried, alert—can be a form of expansion.

Commercial writing, so often pared down, can work the same way and to great effect. Observation means “showing, not just telling”—a principle we writers preach but also often ignore entirely. A good example of this approach in practice comes from Patagonia. Rather than simply stating that its products use “recycled down,” Patagonia's sustainability copy slows the writing–and therefore the reading of the writing–with specifics: “a mix of…600- or 700-fill-power goose and duck down reclaimed from cushions, bedding and other used items that can’t be resold.” By naming the textures of and familiar objects where the down once lived, Patagonia gives its ethics weight and readers a believability that deepens.

Lesson 2: Make the Familiar Strange

The Russian literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky argued that the purpose of art is to restore a kind of freshness to our perception of the world. In daily life, he claimed, perception becomes automatic—we see a tree as just a tree, a house as just a house, a rock as just a rock. Art interrupts this automation. With art, what is habitual is “made strange,” so that it can be seen anew, differently, as if for the first time.

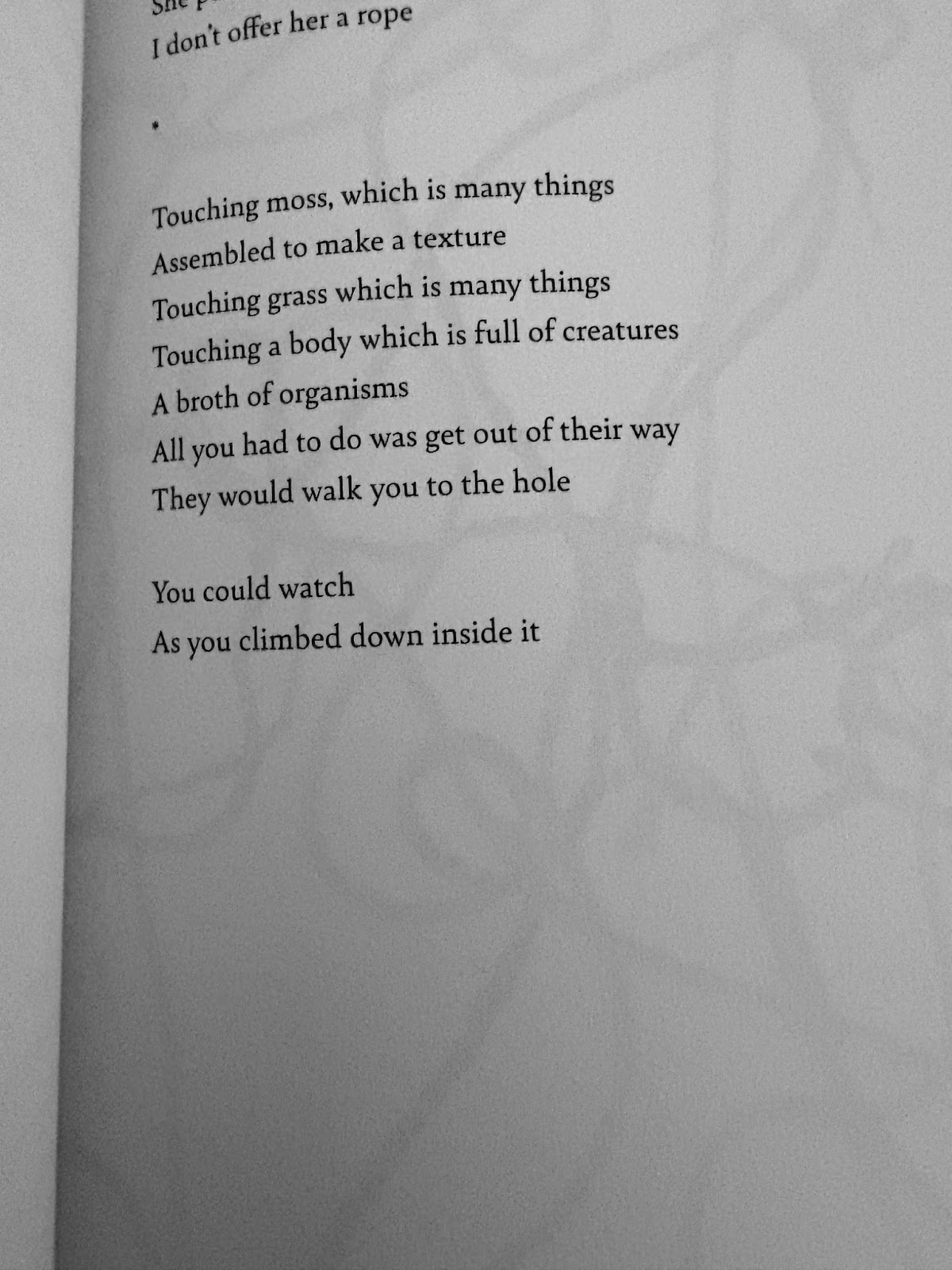

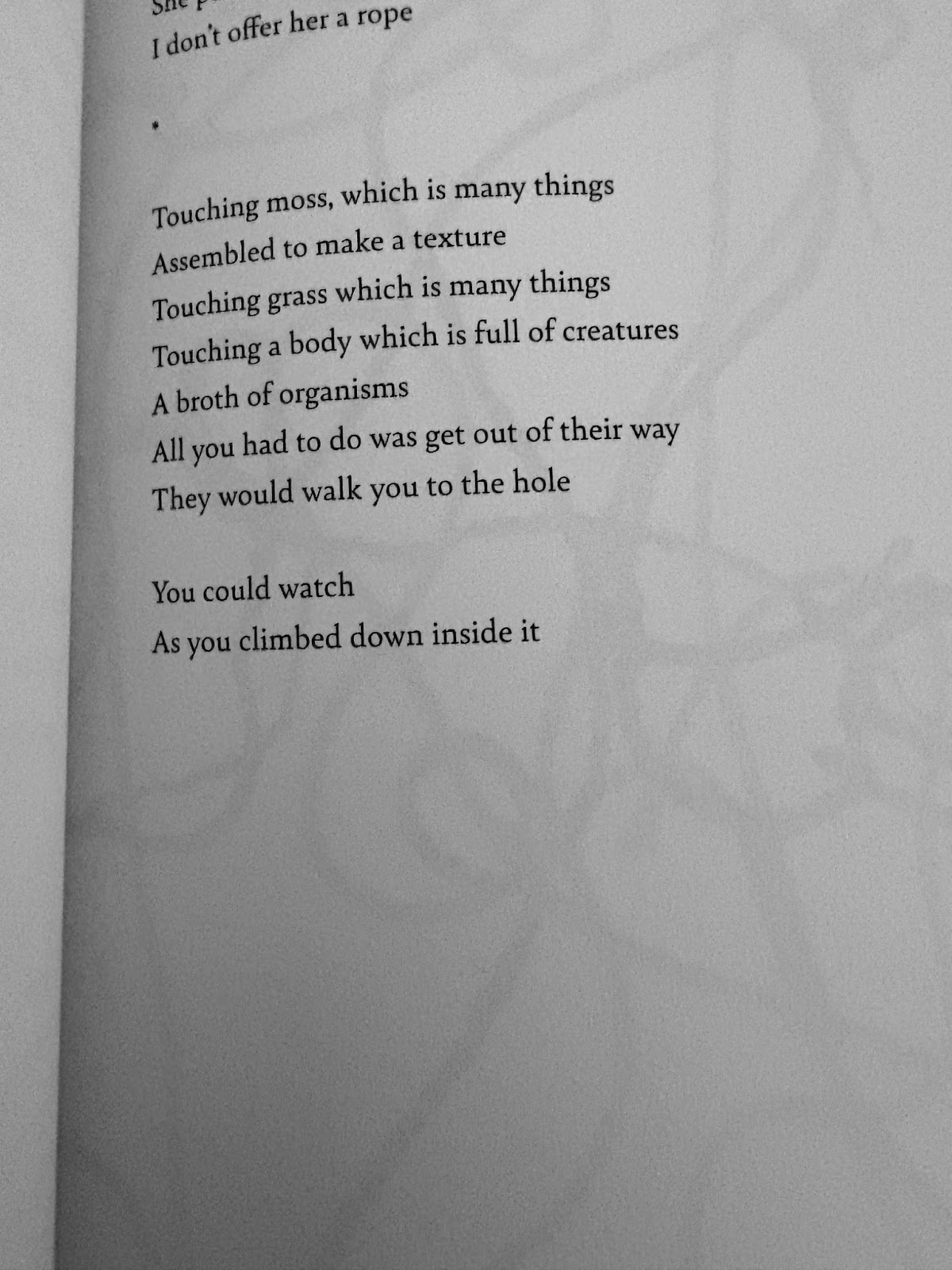

Stephanie Cawley’s “The Hole” from their collection No More Flowers offers a vivid instance of this: taking what seems ordinary and rendering it into something uncanny, ultimately forcing us to attend to it as if for the first time. Toward the end of the poem (pictured below), moss is no longer just moss but “many things / assembled to make a texture,' grass is “many things / touching a body,” and the body itself becomes “a broth of organisms.” What feels like a stable body (the ones we walk around in daily) dissolves into a multiplicity of beings, and eventually the self becomes both watcher and watched, at once known and alien.

Commercial writing, often bent on making the strange familiar, or the familiar even more familiar–can also borrow this technique with striking results. Consider Apple’s famous MacBook campaign line: “Light. Years ahead.” It was audacious at the time, introducing a new version of a product with a twist on language no one had seen before. By breaking apart a familiar idiom, the line forced readers to stop skimming, pause, do a double-take. Suddenly, a phrase we would normally absorb without notice carried more than one meaning, speaking not only to innovation, but to lightness, too.

Lesson 3: Dwell in Complexity

Clarity is the job description for most commercial writers. We’re asked to distill, simplify, even flatten–our messages made to be clean, but also “palatable,” “digestible,” “easy to stomach.” Because of this, Clare Morgan, in her book What Poetry Brings to Business, calls us levelers: communicators who smooth over complexities, sand down ambiguity, eliminate any and all confusion.

According to Morgan, however, poets are the levelers’ opposite. Deemed sharpeners, poets don’t flatten the edges of perception but let every facet gleam individually and even in competition with the other. In other words, poets don’t erase complexity, they heighten it. They invite us into ambiguity, contradiction, and unresolved feeling. This is where John Keats’s notion of negative capability comes in, a concept defined as the ability to remain in uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts without needing to reach for fact, logic, or reason.

Good poems and poets don’t try to make sense of the unknown—they let us sit with it.

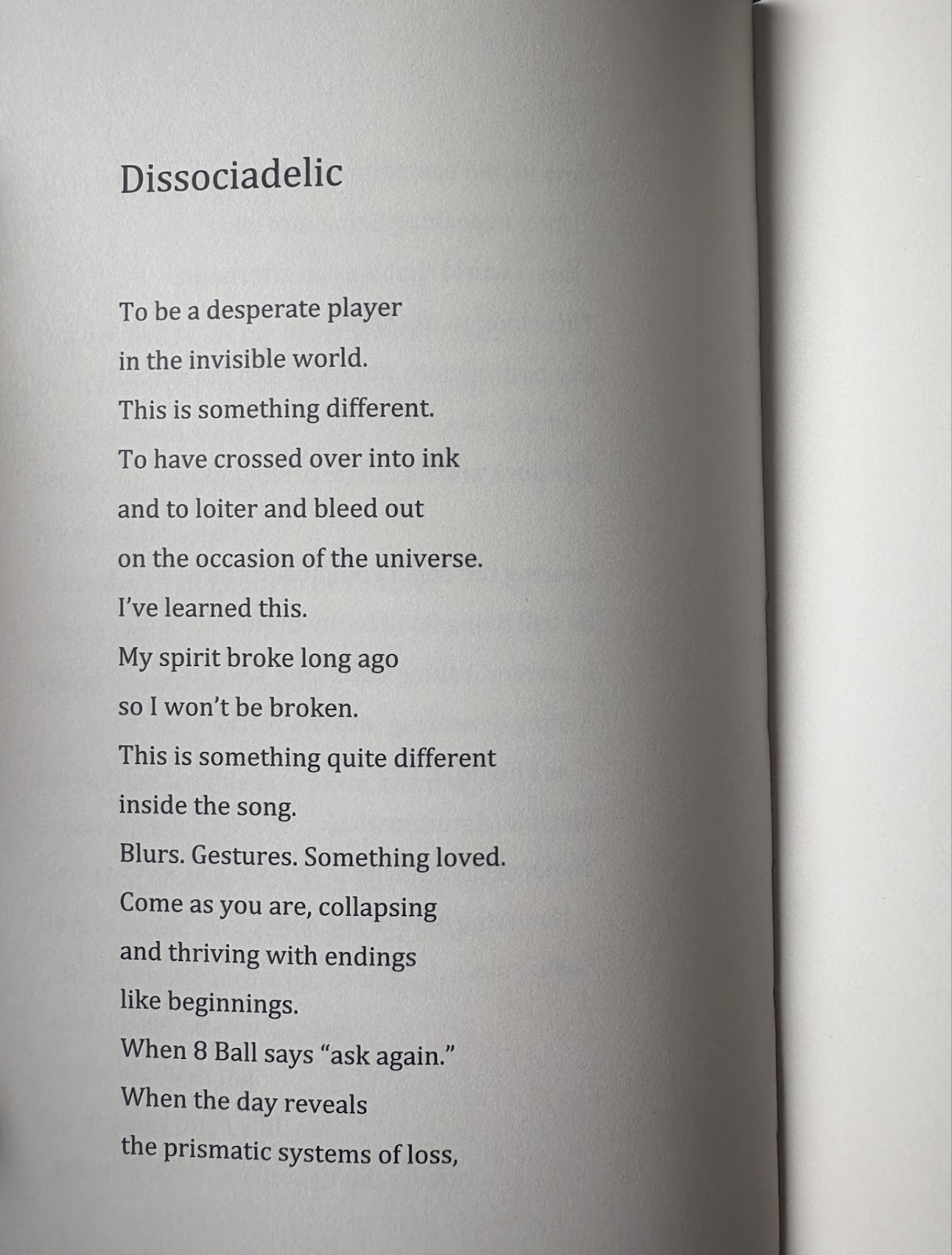

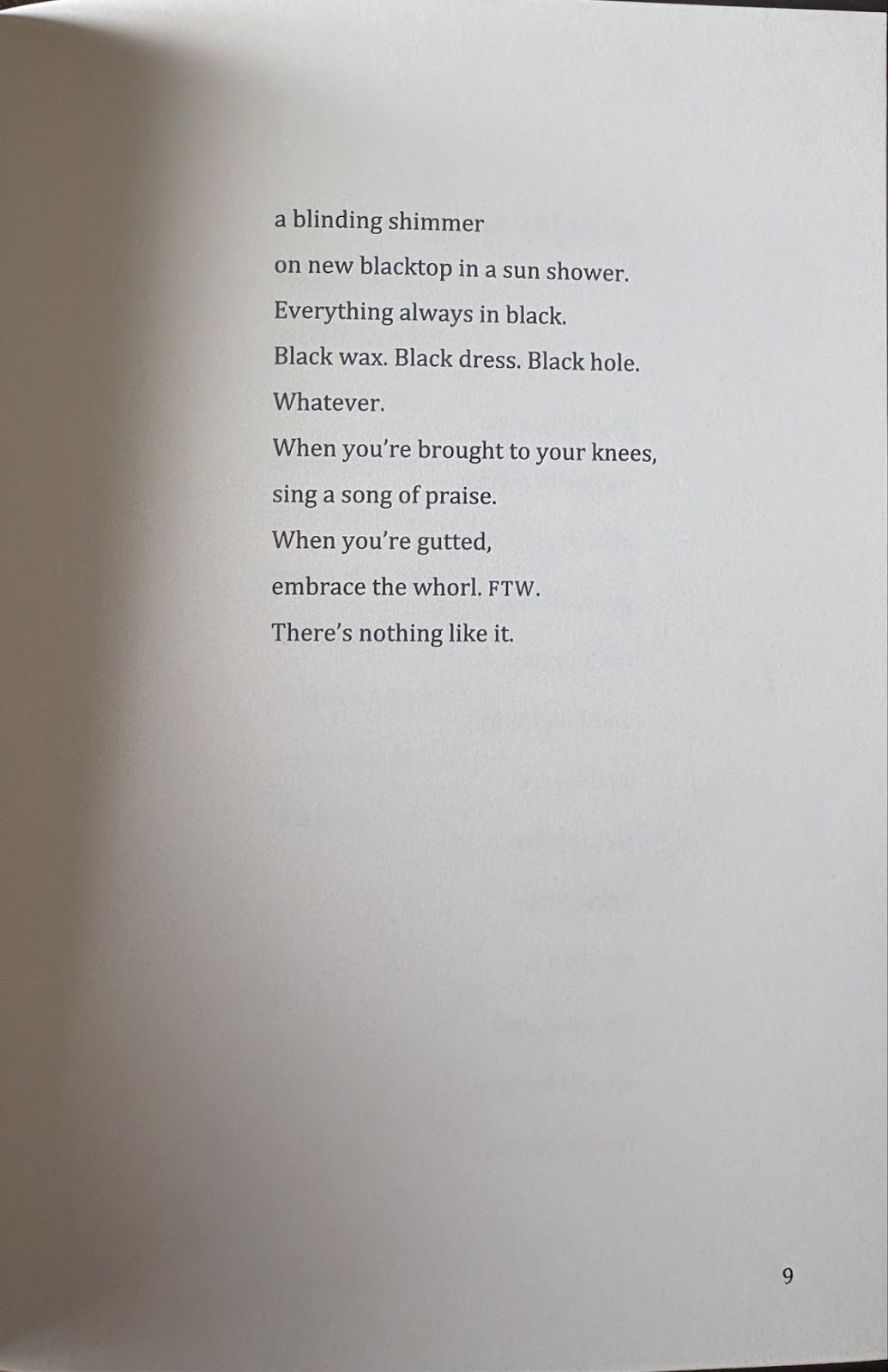

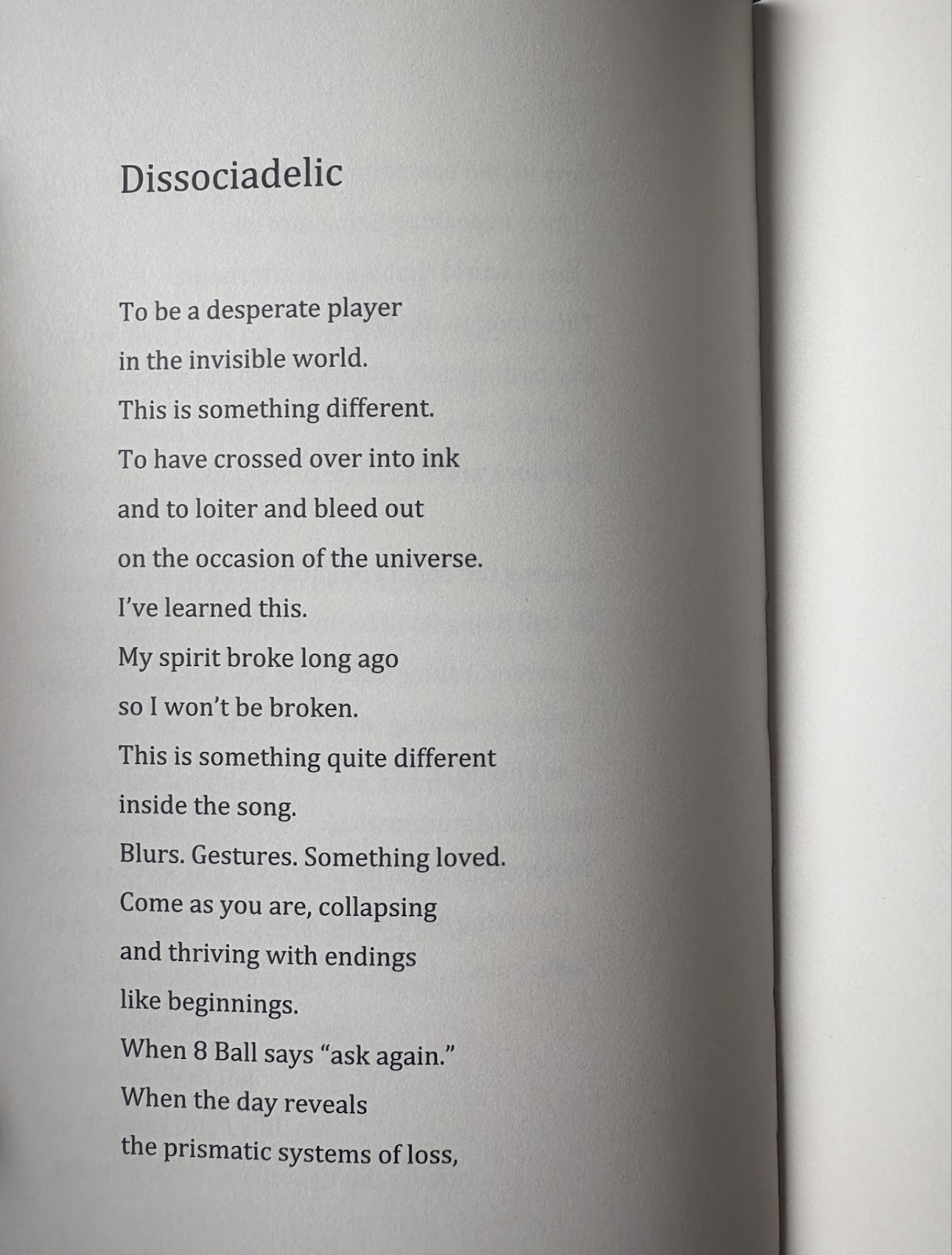

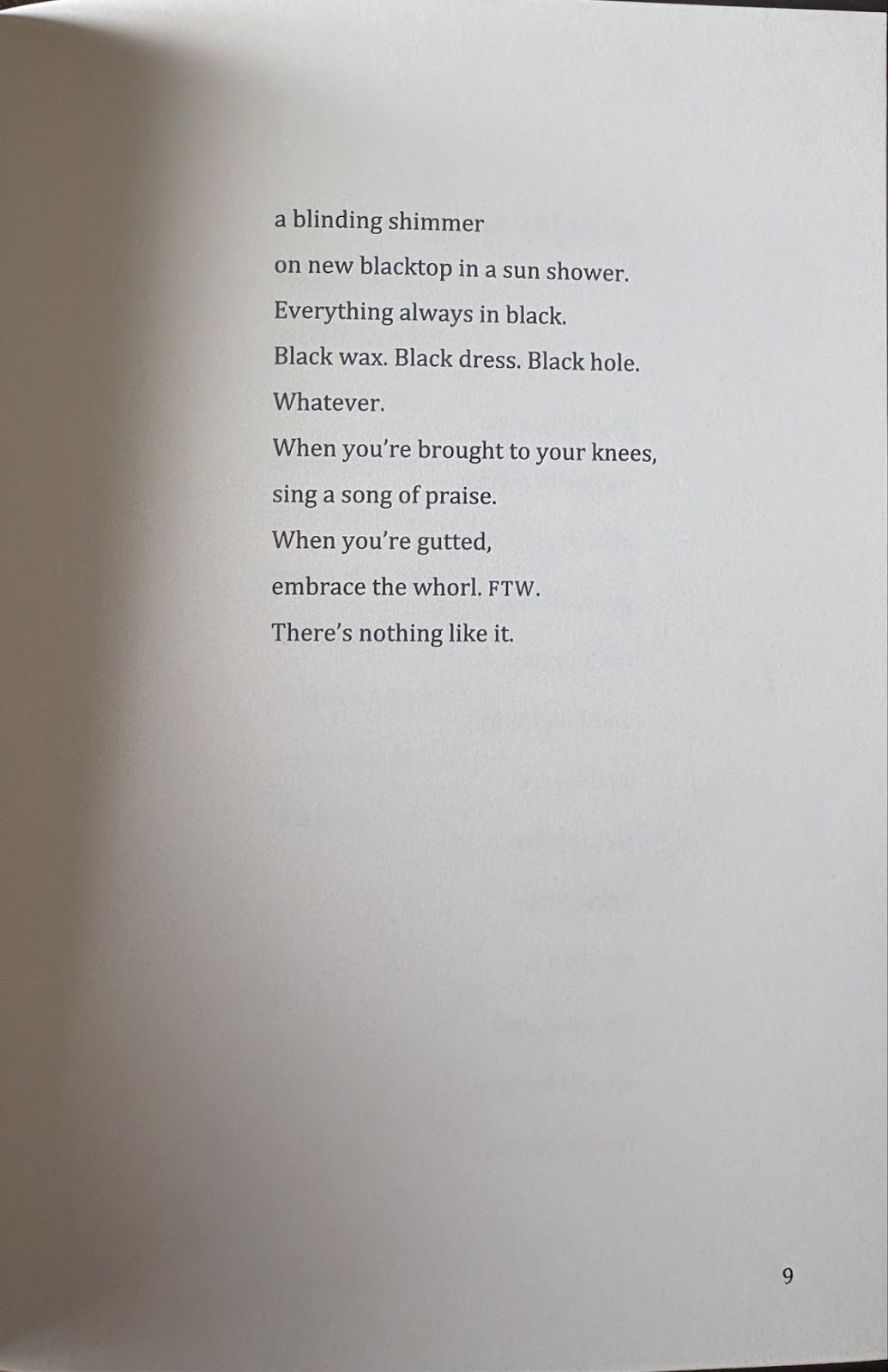

Take Peter Gizzi’s poem “Dissociadelic” (pictured below) from his award-winning collection Fierce Elegy, for instance. The poem feels at once elusive and yet incredible because of its very content and shifting registers—sublime, instructional, digital, which keep us as readers off balance.

In the poem, ambiguity additionally bleeds out. Gizzi layers conditional statements that never remedy (i.e., they are all cause, without effect): “When 8 Ball says ‘ask again.’ / When the day reveals / the prismatic systems of loss…” Images blur and resist explanation, refusing to cohere: “To have crossed over into ink / and to loiter and bleed out / on the occasion of the universe.”

And, rather than clarifying, Gizzi allows contradiction to sit in contradiction. He writes, “Come as you are, collapsing…” Or later: “When you’re gutted, / embrace the whorl. FTW.” The result is language that rebuffs neatness but is simultaneously alive with feeling.

What makes poems like Gizzi's wonderful is that they invite us to be okay with not knowing—and to bring our own thoughts, feelings, and interpretations to what we read. The lesson for commercial writers: extend the same invitation. One way to do this is through open language, as in Nike’s famous “Find Your Greatness” campaign line. It’s a line doesn’t settle into singular meaning but instead leaves space for the reader to step in: “greatness” being anything from running a marathon to starting a business to raising a child to simply getting out of bed after a tough week.

Lesson 4: Play

The New York School poets—e.g., Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Barbara Guest—worked alongside the Abstract Expressionists, painters who didn’t wait for meaning before they made a mark, who painted with spontaneity, joy, mess. And these poets carried that energy into language.

We can look at Frank O’Hara’s “Lana Turner Has Collapsed!” as a paragon of this kind of play. It begins almost absurdly: “Lana Turner has collapsed! / I was trotting along and suddenly / it started raining and snowing…” The tone is campy and casual all at once. And then the poem closes with a near-parasocial gesture, humorously so: “Oh Lana Turner we love you get up.”

Today’s poets take similar cues. For instance, poet Ana Božičević’s “Island” begins with a windfall—“For once in / My life / I got a bit of money / For writing a poem”—before unraveling into bedbugs, beer, LOLs, and jokes with a cat. It doesn’t pretend to be lofty or especially refined. And yet, by its end—“This poem sucks / Cause I’m so happy,” the poem is incredibly profound and speaks to a universal feeling.

These poems and poets remind us that play and spontaneity aren’t detours from or detractors of meaning. They’re often the very path to it. Trying your hand at poetry can teach you that there is no right or wrong. Humor isn’t just humor—it can unite, stun, disarm. The mess isn’t just a mess but full of relevant threads. And the sandboxes we make for ourselves–they don’t have to be sandboxes at all. To grow as writers, all we need to do is loosen the language, embrace the ride–much like Gizzi’s whorl, and see what might unfurl.

My invitation to you this week: observe before you pick up the pen, write as if seeing something for the very first time, or let ambiguity breathe. Better yet, simply play!

Stevie Belchak is a freelance namer, strategist, and writer living in San Jose, Costa Rica. When she's not wording out for work, she edits for blush lit and writes out of love—publishing poetry and essays in journals, across the web, and through her Substack, Mother Of.

As commercial writers, we lean on what we know—familiar phrases, recycled metaphors, industry clichés, because they’re efficient. And today’s AI tools, trained on vast corpora of human language, don’t just echo these habits but reinforce them, keeping us in what can feel like an infinite loop.

Poetry, however, asks for the opposite.

Poetry invites us to break the line. It asks us to collide nouns and modifiers into happy accidents that sing. It asks us to create imagery that feels impossible and new–think: Hunter Larson’s “mouth of the countryside” (pictured below) or Cynthia Cruz’s “mink / Lined winter.” It asks us to pause, to examine, to make the ordinary strange. To write a window, then open it, and step outside.

This month I had the pleasure of teaching How to Build Your Writing Muscle Through Poetic Practice. The group that Zoomed in was made up of copywriters, brand storytellers, marketers, and journalists—people who, like me, spend their days inside voice and tone guidelines and client constraints. Together we lifted out of words’ well-worn grooves, to see what else language could do. Specifically, we took a page out of poetry’s book to understand language’s infinite possibilities.

These were the lessons shared, the ones we can borrow as commercial writers. Some might call them small apertures into a new way of doing what we love, others: Miracle-Gro for our writerly minds.

Lesson 1: Slow Down

In our professional roles, we’re trained to critique, fix, resolve—and above all, to “get to the point.” But poetry reminds us that meaning often emerges not from efficiency but from slowing down.

The French philosopher Simone Weil once said, “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” Much of poetry embodies that generosity—it lingers on the ordinary, noticing what might otherwise pass unseen.

One of James Schuyler’s famed Payne Whitney poems is a poem that does just that. What’s striking about “Sleep” is that the speaker doesn’t appear until the final line (“Give my love to, oh, anybody”). What precedes it is a poem gathered in fragments and one of pure description. There are tangerines, a doily, a pierced ear, an overheard conversation, heart-shaped cookies, a crescent moon. Nothing is extraordinary, and yet, through the attention given to each detail, each detail becomes exceptional, luminous. In this way, the poem suggests that perception itself—patient, unhurried, alert—can be a form of expansion.

Commercial writing, so often pared down, can work the same way and to great effect. Observation means “showing, not just telling”—a principle we writers preach but also often ignore entirely. A good example of this approach in practice comes from Patagonia. Rather than simply stating that its products use “recycled down,” Patagonia's sustainability copy slows the writing–and therefore the reading of the writing–with specifics: “a mix of…600- or 700-fill-power goose and duck down reclaimed from cushions, bedding and other used items that can’t be resold.” By naming the textures of and familiar objects where the down once lived, Patagonia gives its ethics weight and readers a believability that deepens.

Lesson 2: Make the Familiar Strange

The Russian literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky argued that the purpose of art is to restore a kind of freshness to our perception of the world. In daily life, he claimed, perception becomes automatic—we see a tree as just a tree, a house as just a house, a rock as just a rock. Art interrupts this automation. With art, what is habitual is “made strange,” so that it can be seen anew, differently, as if for the first time.

Stephanie Cawley’s “The Hole” from their collection No More Flowers offers a vivid instance of this: taking what seems ordinary and rendering it into something uncanny, ultimately forcing us to attend to it as if for the first time. Toward the end of the poem (pictured below), moss is no longer just moss but “many things / assembled to make a texture,' grass is “many things / touching a body,” and the body itself becomes “a broth of organisms.” What feels like a stable body (the ones we walk around in daily) dissolves into a multiplicity of beings, and eventually the self becomes both watcher and watched, at once known and alien.

Commercial writing, often bent on making the strange familiar, or the familiar even more familiar–can also borrow this technique with striking results. Consider Apple’s famous MacBook campaign line: “Light. Years ahead.” It was audacious at the time, introducing a new version of a product with a twist on language no one had seen before. By breaking apart a familiar idiom, the line forced readers to stop skimming, pause, do a double-take. Suddenly, a phrase we would normally absorb without notice carried more than one meaning, speaking not only to innovation, but to lightness, too.

Lesson 3: Dwell in Complexity

Clarity is the job description for most commercial writers. We’re asked to distill, simplify, even flatten–our messages made to be clean, but also “palatable,” “digestible,” “easy to stomach.” Because of this, Clare Morgan, in her book What Poetry Brings to Business, calls us levelers: communicators who smooth over complexities, sand down ambiguity, eliminate any and all confusion.

According to Morgan, however, poets are the levelers’ opposite. Deemed sharpeners, poets don’t flatten the edges of perception but let every facet gleam individually and even in competition with the other. In other words, poets don’t erase complexity, they heighten it. They invite us into ambiguity, contradiction, and unresolved feeling. This is where John Keats’s notion of negative capability comes in, a concept defined as the ability to remain in uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts without needing to reach for fact, logic, or reason.

Good poems and poets don’t try to make sense of the unknown—they let us sit with it.

Take Peter Gizzi’s poem “Dissociadelic” (pictured below) from his award-winning collection Fierce Elegy, for instance. The poem feels at once elusive and yet incredible because of its very content and shifting registers—sublime, instructional, digital, which keep us as readers off balance.

In the poem, ambiguity additionally bleeds out. Gizzi layers conditional statements that never remedy (i.e., they are all cause, without effect): “When 8 Ball says ‘ask again.’ / When the day reveals / the prismatic systems of loss…” Images blur and resist explanation, refusing to cohere: “To have crossed over into ink / and to loiter and bleed out / on the occasion of the universe.”

And, rather than clarifying, Gizzi allows contradiction to sit in contradiction. He writes, “Come as you are, collapsing…” Or later: “When you’re gutted, / embrace the whorl. FTW.” The result is language that rebuffs neatness but is simultaneously alive with feeling.

What makes poems like Gizzi's wonderful is that they invite us to be okay with not knowing—and to bring our own thoughts, feelings, and interpretations to what we read. The lesson for commercial writers: extend the same invitation. One way to do this is through open language, as in Nike’s famous “Find Your Greatness” campaign line. It’s a line doesn’t settle into singular meaning but instead leaves space for the reader to step in: “greatness” being anything from running a marathon to starting a business to raising a child to simply getting out of bed after a tough week.

Lesson 4: Play

The New York School poets—e.g., Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Barbara Guest—worked alongside the Abstract Expressionists, painters who didn’t wait for meaning before they made a mark, who painted with spontaneity, joy, mess. And these poets carried that energy into language.

We can look at Frank O’Hara’s “Lana Turner Has Collapsed!” as a paragon of this kind of play. It begins almost absurdly: “Lana Turner has collapsed! / I was trotting along and suddenly / it started raining and snowing…” The tone is campy and casual all at once. And then the poem closes with a near-parasocial gesture, humorously so: “Oh Lana Turner we love you get up.”

Today’s poets take similar cues. For instance, poet Ana Božičević’s “Island” begins with a windfall—“For once in / My life / I got a bit of money / For writing a poem”—before unraveling into bedbugs, beer, LOLs, and jokes with a cat. It doesn’t pretend to be lofty or especially refined. And yet, by its end—“This poem sucks / Cause I’m so happy,” the poem is incredibly profound and speaks to a universal feeling.

These poems and poets remind us that play and spontaneity aren’t detours from or detractors of meaning. They’re often the very path to it. Trying your hand at poetry can teach you that there is no right or wrong. Humor isn’t just humor—it can unite, stun, disarm. The mess isn’t just a mess but full of relevant threads. And the sandboxes we make for ourselves–they don’t have to be sandboxes at all. To grow as writers, all we need to do is loosen the language, embrace the ride–much like Gizzi’s whorl, and see what might unfurl.

My invitation to you this week: observe before you pick up the pen, write as if seeing something for the very first time, or let ambiguity breathe. Better yet, simply play!

Stevie Belchak is a freelance namer, strategist, and writer living in San Jose, Costa Rica. When she's not wording out for work, she edits for blush lit and writes out of love—publishing poetry and essays in journals, across the web, and through her Substack, Mother Of.