At their core, brand stories are mirrors. They connect people to stories - reflecting what broader culture values, aspires to, and believes about the world. Some of the most memorable brand stories are ones that push culture by amplifying its most promising and progressive forces, most brands reflect the world exactly as it is - reproducing trends, biases, and social hierarchies.

Gender and Brand is a three-part series unpacking how gender has shaped brand identity and storytelling—how early advertising built entire brand worlds around gender, how brands have tried to rewrite those narratives, and what that influence means for the brands being built today.

In this first installment, we’ll look at mid-century examples of brands that wove gender into their brand identity. This binary set the stage for how brands operate today—either in opposition to these ideals or, more recently, in a comfortable regression back to them.

Women are pictured primarily in two recurring roles: as the housewife, positioned as a flawless champion of the domestic sphere, and the accessory, valued only as a status symbol in proximity to men.

Feminine Performance as Accessory

Marlboro epitomizes the fluidity of gender interpretations in branding and how easily a brand can further entrench sexism through their portrayals. Today, the brand is recognized for symbolizing masculinity through a story of freedom and adventure. But the brand’s earlier campaigns started with women as their primary target.

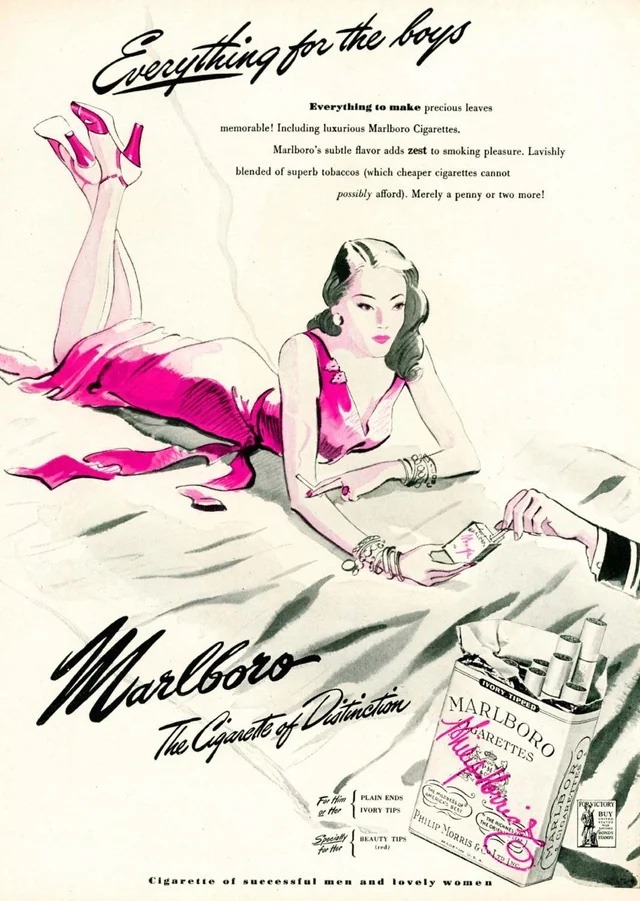

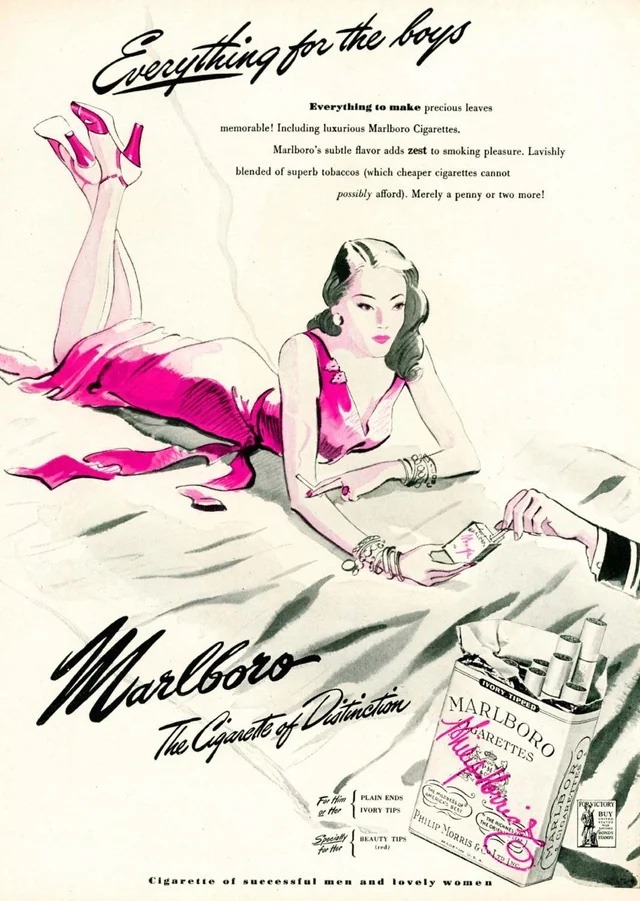

In this series of ads from the 40s,’ women are the focus of the visuals but aren’t the true center of the story. Instead, they are depicted as accessories to men.

The term “sex object” often describes women’s portrayals in this era’s advertising—but this idea can be folded into the broader accessory category. Not all objectification is sexual. Just as often, women are used like cars or watches, their image raising a men’s perceived social status.

The line “everything for the boys” leaves little room for interpretation. These ads target women through their desire to appeal to men, positioning the ideal woman in a secondary social role—encoding the idea of women as subservient characters in a man’s world.

The visuals also work in tandem with the language. Cursive fonts and soft color palettes signal softness and refinement.

The line “the cigarette for successful men and lovely women” perfectly exemplifies the binary being drawn between the genders. The aspirational quality “lovely” is assigned and consumed, while “successful” is embodied.

Product variants are specifically gendered, ivory-tipped cigarettes as “for both men and women,” and red “beauty tips” marketed “specially for her.”

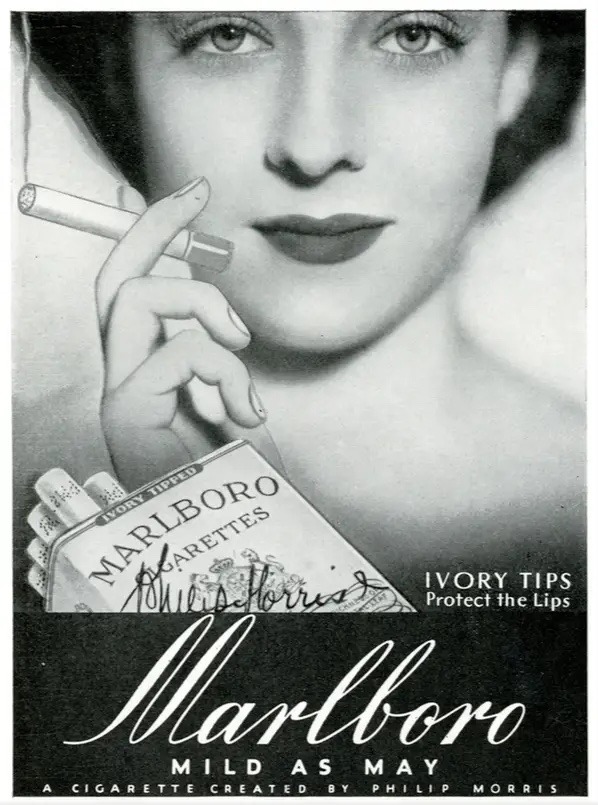

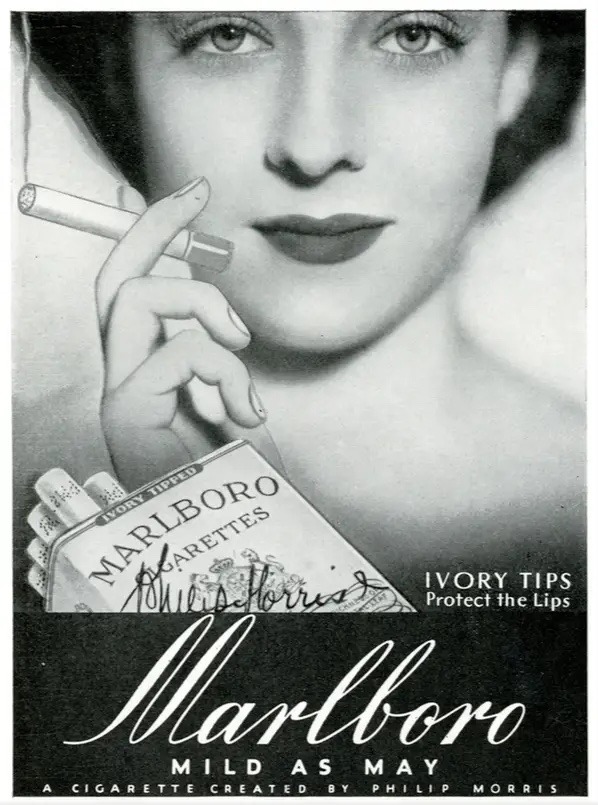

But in another ad, the ivory tipped cigarettes are aligned with the tagline “Mild as May” and only marketed towards women.

This example of different gendered interpretations of the same product variant shows how in this campaign, gender was an even more prominent tool in Marlboro’s brand positioning than the actual product itself. The sexist cultural box women were placed in persisted so strongly that it made sense for the brand to contract its original story as long as it was in alignment with the prominent gendered narrative.

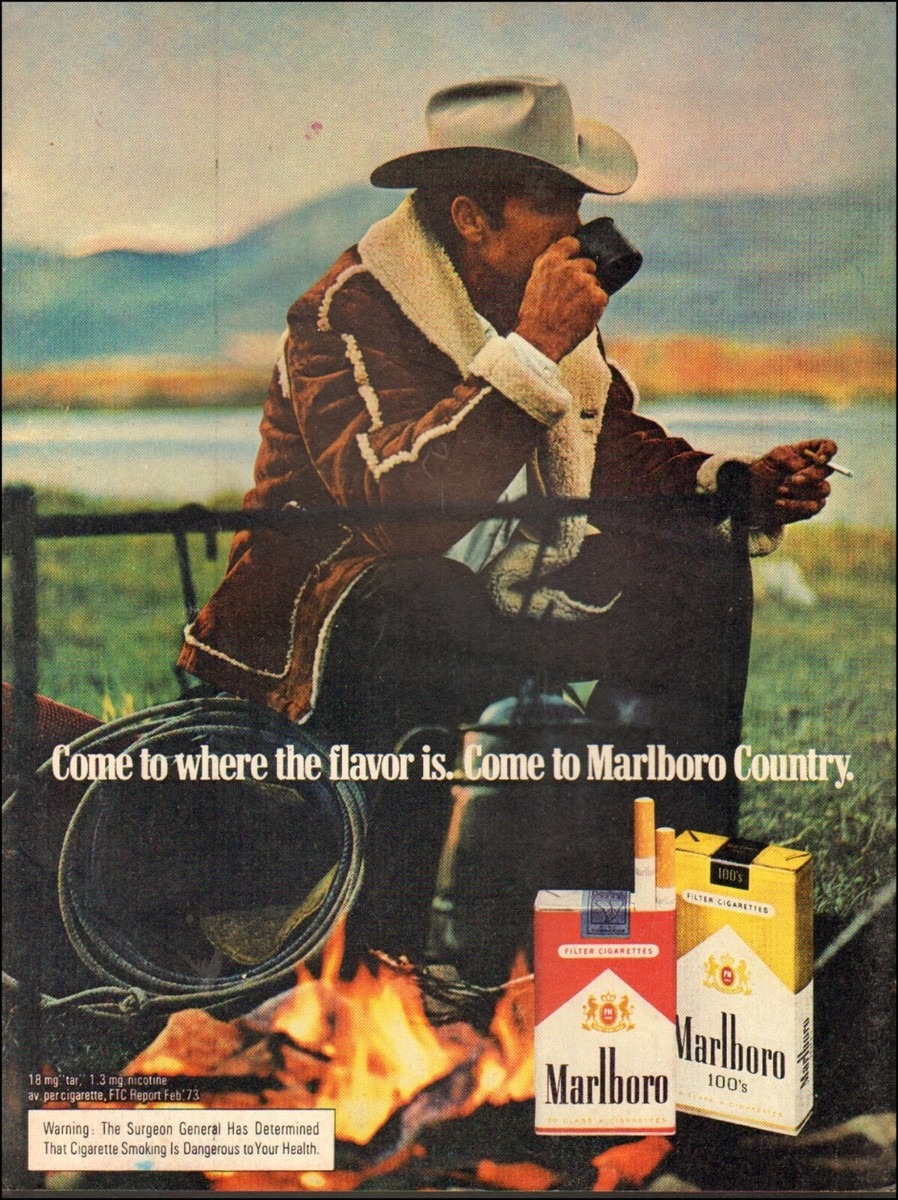

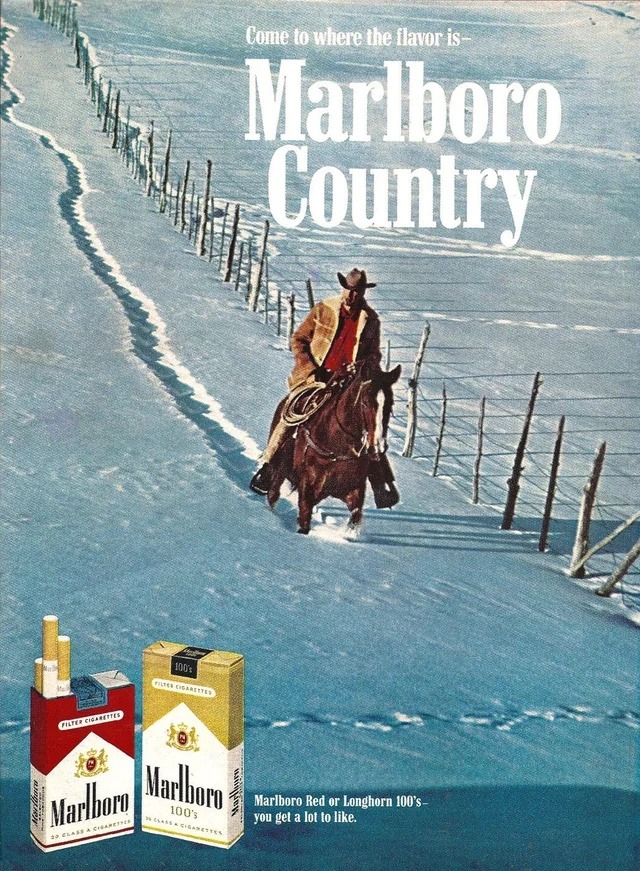

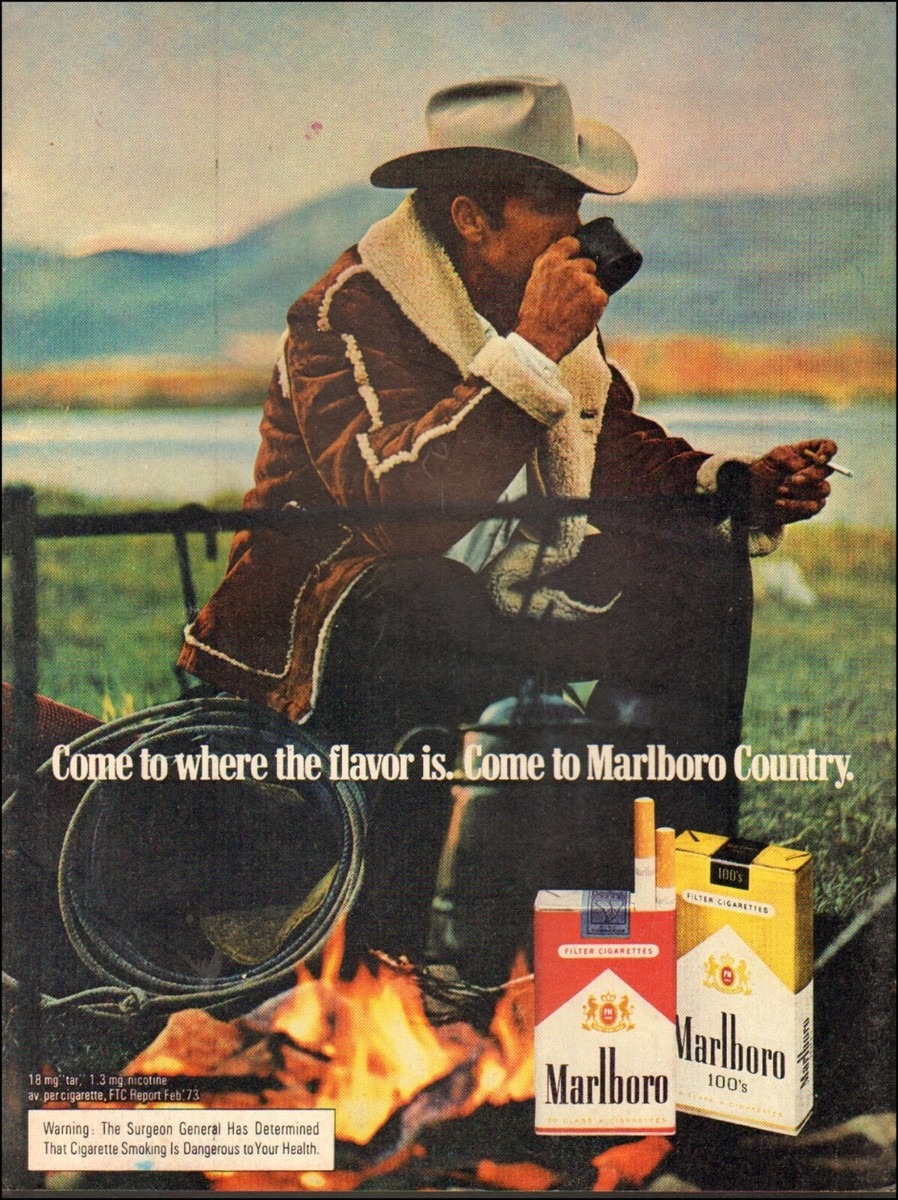

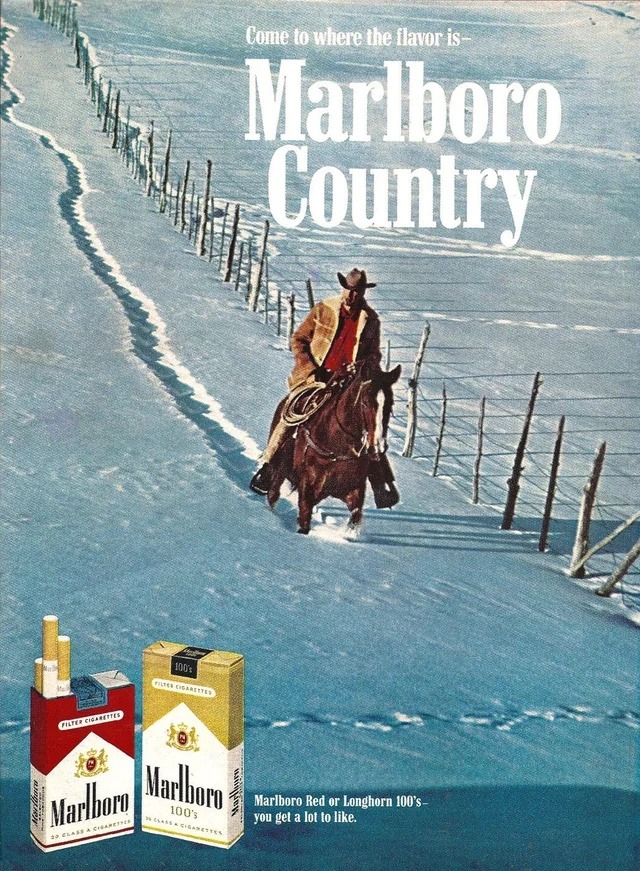

Marlboro’s brand story evolved to take women mostly out of the equation in favor of portraying a different gendered story: the Marlboro Man. This figure symbolized stoicism and independence from rigidity and routine, the ultimate symbol of masculine freedom and individualism. Delicate cursive fonts shifted to the bold, imposing font Marlboro is known for today. “Come to where the flavor is” serves as an active call to action, signaling agency over passivity.

A wry comment from a Reddit user puts it pretty well,

“Back when men were men. Bronc busting, saddlesweat, sharing a small tent on the open range, learning the mysteries of love on the prairie, and getting some sweet western lung cancer. The good old days.”

The Marlboro Man and Marlboro brand as a whole represent another side of a gendered fantasy, one where rugged masculinity is put on a pedestal by romanticizing a lone-wolf kind of independence.

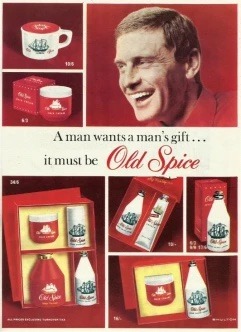

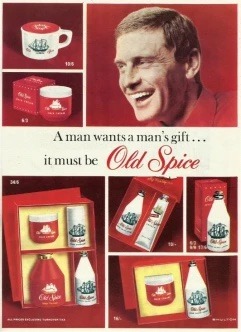

Old Spice shows another example of how mid-century brands embedded masculinity as its own rigid performance. While women are chained to their ties to domesticity, men are framed as self regulating, stoic figures whose value comes from their authority and leadership.

The line “A man wants a man’s gift… it must be Old Spice” shows that this masculine freedom doesn’t come without conditions. It must be proven. The brand’s imagery shows masculinity as a delicate balance between roughness and refinement. Old Spice is a means of obtaining a coveted level of polish without sacrificing the emotional distance to be taken seriously as a man.

Idealized Domestic Duty

Mid-century gender roles were shaped by the nuclear family and rigid expectations about domestic labor. In this portrayal, women are either accessories to men or domestic caretakers. Often, both of these roles would be prescribed to women based on their age and stage of life.

Ponds positions the aspirational woman as one tied to marriage, which at the time almost always implied a future as a housewife. Lines like “Pond’s girls belong to cupid” reinforce the idea that a woman’s value comes from their proximity to men and a family.

Ponds shows how portraying women as accessories and housewives is more of a timeline than a dichotomy. A woman’s beauty makes her an accessory, and her marriage status makes her a force of labor.

Tide further develops the feminine counterpart of the “housewife” by going full force on tying women’s identities to the domestic labor they perform, in addition to their proximity to their families and husbands.

Strong lines like “No wonder women are in love with that wonderful Tide” exaggerate, almost mock, the ideal of a woman cheerfully performing the gendered work she has little choice but to partake in. The visuals mirror the same domestic joy.

Women are also portrayed directly in relation to the family: representing a narrow vision of women’s position as caretakers and servants of the household. Their performative happiness feeds into the fantasy that women are naturally inclined to this role, and should be happy to fulfil it.

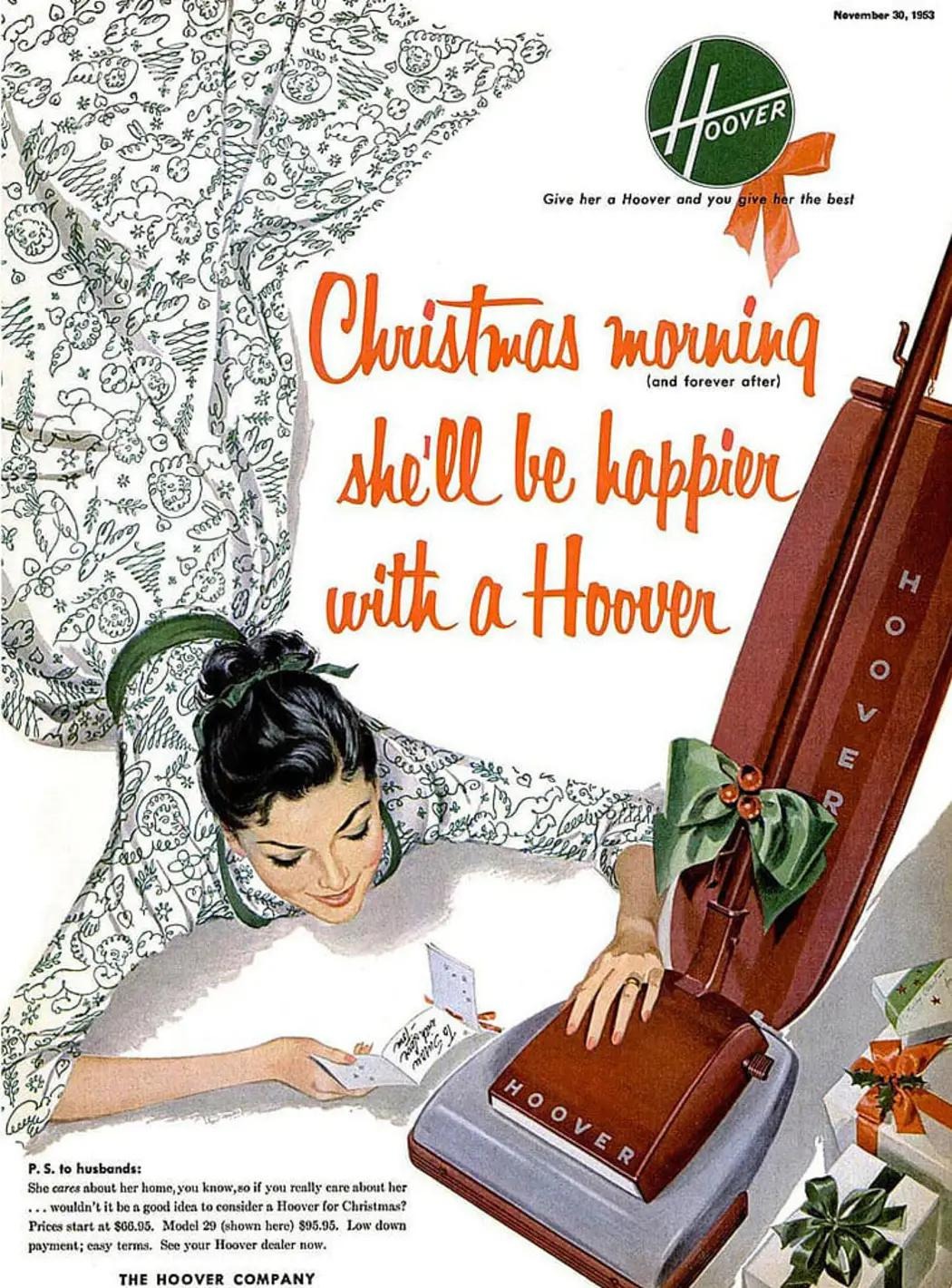

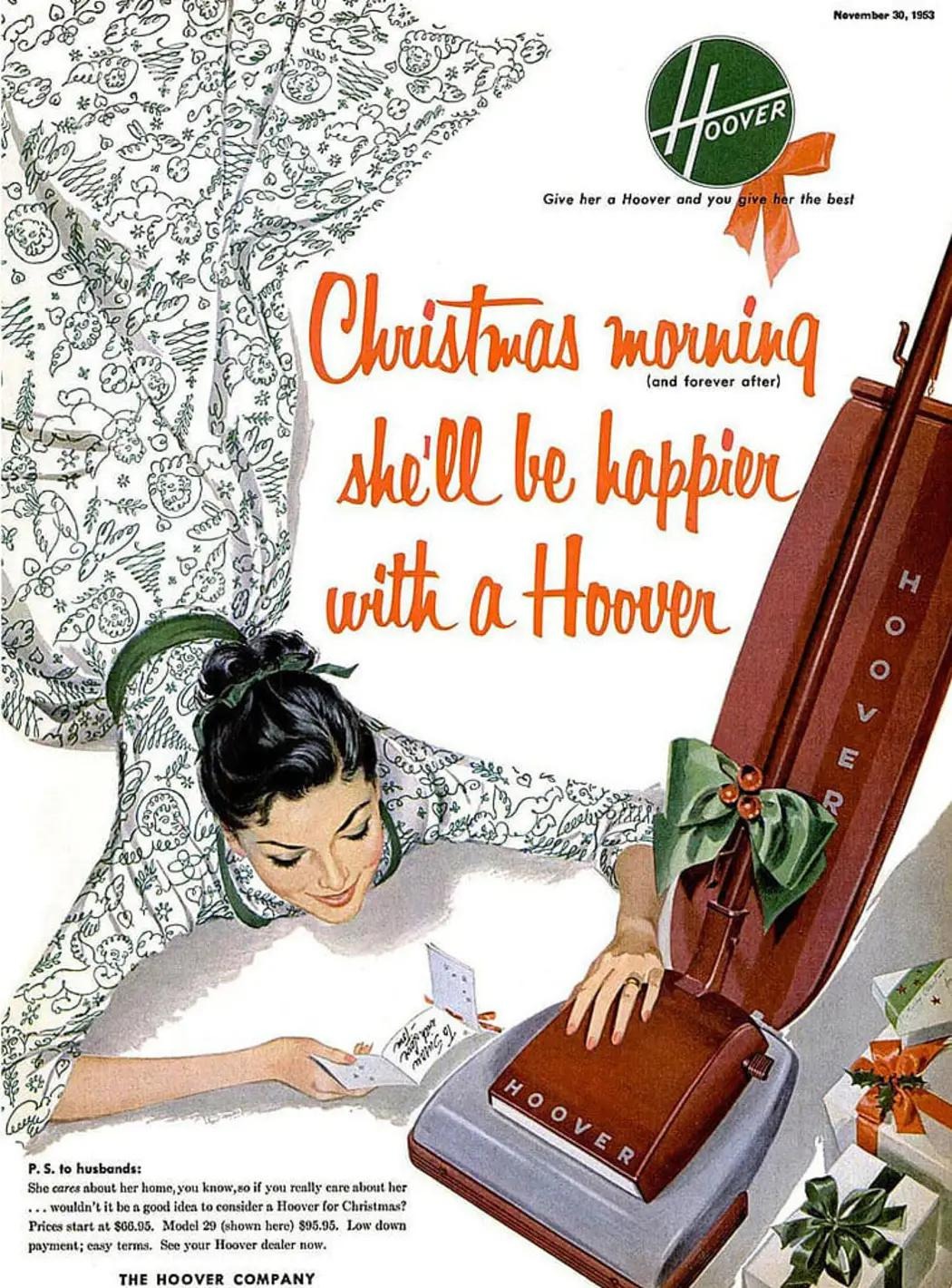

Hoover took a similar approach with this Christmas ad. The ad speaks directly to husbands, who are the primary audience for the purchase of the vacuum and the fantasy that their wives exist as servants of the home who would be happy to celebrate the holidays with a new tool related to this role.

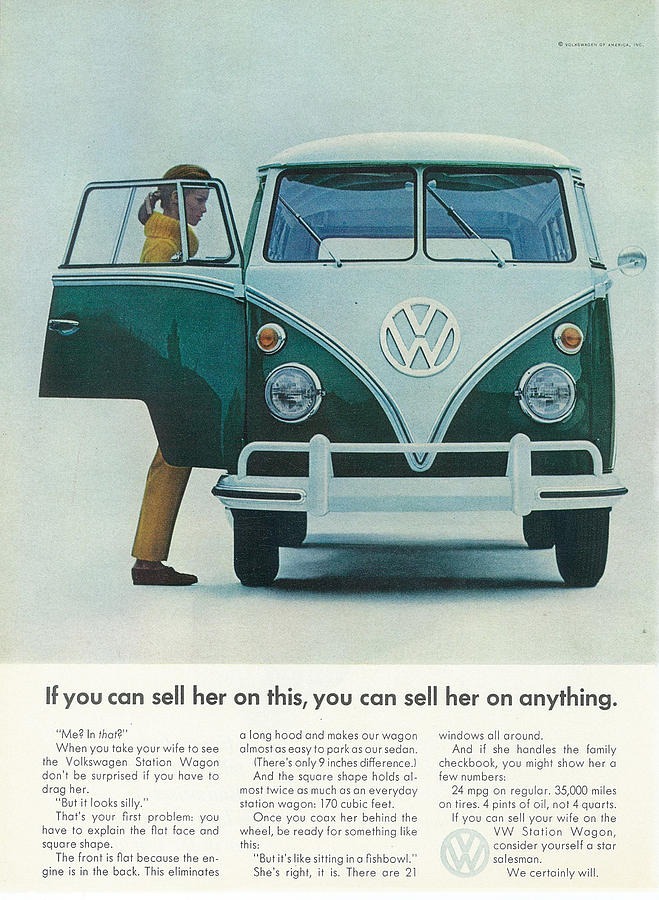

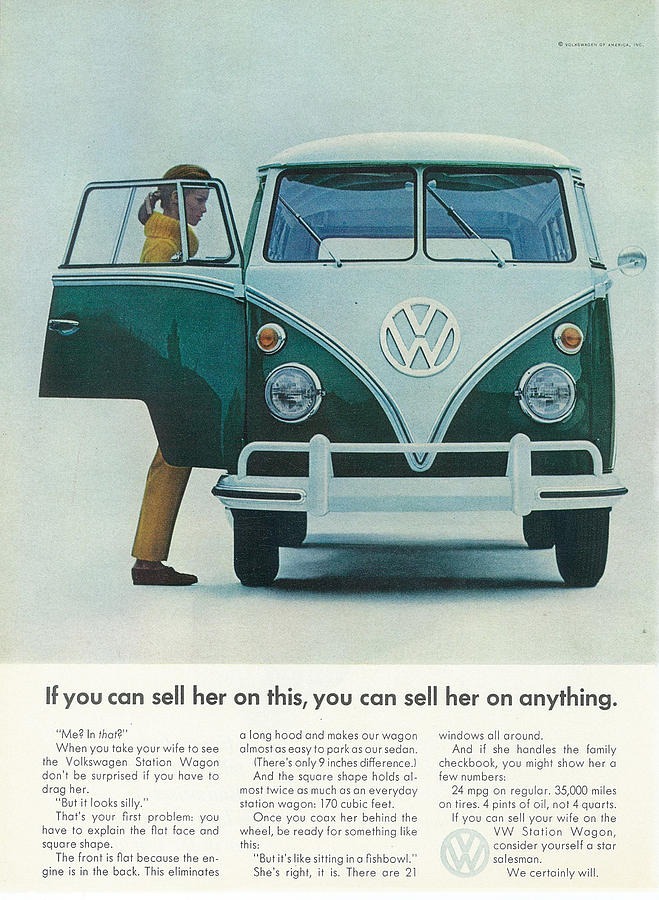

In the 1970s, the Volkswagen brand expanded on a similar messaging strategy, reworked to fit the era. Their station wagon ads (although these were cars marketed towards families) subtly condescended to women. Volkswagen makes it clear that men are their primary audience by speaking about women rather than speaking to them. Lines like “If you can sell her on this, you can sell her on anything” assume a male reader and reinforce a hierarchy where men are insiders and decision-makers, and women are obstacles in their way.

As a result, the minimalist but captivating tone the brand is known for aligns itself with masculinity, alienating women from being insiders to the brand’s world or equal decision makers in the household.

The line “mommy’s big helper” also speaks down, shifting gears from the car’s technical features to invoking an idealized image of a cheerful, dutiful housewife. It may seem like a wholesome image, but when examined in context, it becomes apparent that it’s rooted in a gendered fantasy that serves male power.

Both Tide and Volkswagen both perpetuate gendered roles within the family in subtly different flavors based on the social scripts of the time. Tide reflected cheerfulness and service as ideal feminine virtues, and Volkswagen reflected a similar message expanding upon it by framing condescension toward women as humor.

The archetypes of accessory, housewife, and the masculine individualist set a default template for how gender shows up in brand storytelling today. These narratives outlived any one product or brand identity, embedding the era’s gendered ideas into the foundation of branding, in turn entrenching them into culture itself.

In the next installment of Gender and Brand, we’ll explore examples of brands trying to push back against these established scripts—and what it means to tell a story that truly diverts from these foundations.

Izzy Colón is a culture writer, creative copywriter, and Contributing Writer for The Subtext. She lives in Chicago, where she spends as much time collecting stories as she does writing them.

At their core, brand stories are mirrors. They connect people to stories - reflecting what broader culture values, aspires to, and believes about the world. Some of the most memorable brand stories are ones that push culture by amplifying its most promising and progressive forces, most brands reflect the world exactly as it is - reproducing trends, biases, and social hierarchies.

Gender and Brand is a three-part series unpacking how gender has shaped brand identity and storytelling—how early advertising built entire brand worlds around gender, how brands have tried to rewrite those narratives, and what that influence means for the brands being built today.

In this first installment, we’ll look at mid-century examples of brands that wove gender into their brand identity. This binary set the stage for how brands operate today—either in opposition to these ideals or, more recently, in a comfortable regression back to them.

Women are pictured primarily in two recurring roles: as the housewife, positioned as a flawless champion of the domestic sphere, and the accessory, valued only as a status symbol in proximity to men.

Feminine Performance as Accessory

Marlboro epitomizes the fluidity of gender interpretations in branding and how easily a brand can further entrench sexism through their portrayals. Today, the brand is recognized for symbolizing masculinity through a story of freedom and adventure. But the brand’s earlier campaigns started with women as their primary target.

In this series of ads from the 40s,’ women are the focus of the visuals but aren’t the true center of the story. Instead, they are depicted as accessories to men.

The term “sex object” often describes women’s portrayals in this era’s advertising—but this idea can be folded into the broader accessory category. Not all objectification is sexual. Just as often, women are used like cars or watches, their image raising a men’s perceived social status.

The line “everything for the boys” leaves little room for interpretation. These ads target women through their desire to appeal to men, positioning the ideal woman in a secondary social role—encoding the idea of women as subservient characters in a man’s world.

The visuals also work in tandem with the language. Cursive fonts and soft color palettes signal softness and refinement.

The line “the cigarette for successful men and lovely women” perfectly exemplifies the binary being drawn between the genders. The aspirational quality “lovely” is assigned and consumed, while “successful” is embodied.

Product variants are specifically gendered, ivory-tipped cigarettes as “for both men and women,” and red “beauty tips” marketed “specially for her.”

But in another ad, the ivory tipped cigarettes are aligned with the tagline “Mild as May” and only marketed towards women.

This example of different gendered interpretations of the same product variant shows how in this campaign, gender was an even more prominent tool in Marlboro’s brand positioning than the actual product itself. The sexist cultural box women were placed in persisted so strongly that it made sense for the brand to contract its original story as long as it was in alignment with the prominent gendered narrative.

Marlboro’s brand story evolved to take women mostly out of the equation in favor of portraying a different gendered story: the Marlboro Man. This figure symbolized stoicism and independence from rigidity and routine, the ultimate symbol of masculine freedom and individualism. Delicate cursive fonts shifted to the bold, imposing font Marlboro is known for today. “Come to where the flavor is” serves as an active call to action, signaling agency over passivity.

A wry comment from a Reddit user puts it pretty well,

“Back when men were men. Bronc busting, saddlesweat, sharing a small tent on the open range, learning the mysteries of love on the prairie, and getting some sweet western lung cancer. The good old days.”

The Marlboro Man and Marlboro brand as a whole represent another side of a gendered fantasy, one where rugged masculinity is put on a pedestal by romanticizing a lone-wolf kind of independence.

Old Spice shows another example of how mid-century brands embedded masculinity as its own rigid performance. While women are chained to their ties to domesticity, men are framed as self regulating, stoic figures whose value comes from their authority and leadership.

The line “A man wants a man’s gift… it must be Old Spice” shows that this masculine freedom doesn’t come without conditions. It must be proven. The brand’s imagery shows masculinity as a delicate balance between roughness and refinement. Old Spice is a means of obtaining a coveted level of polish without sacrificing the emotional distance to be taken seriously as a man.

Idealized Domestic Duty

Mid-century gender roles were shaped by the nuclear family and rigid expectations about domestic labor. In this portrayal, women are either accessories to men or domestic caretakers. Often, both of these roles would be prescribed to women based on their age and stage of life.

Ponds positions the aspirational woman as one tied to marriage, which at the time almost always implied a future as a housewife. Lines like “Pond’s girls belong to cupid” reinforce the idea that a woman’s value comes from their proximity to men and a family.

Ponds shows how portraying women as accessories and housewives is more of a timeline than a dichotomy. A woman’s beauty makes her an accessory, and her marriage status makes her a force of labor.

Tide further develops the feminine counterpart of the “housewife” by going full force on tying women’s identities to the domestic labor they perform, in addition to their proximity to their families and husbands.

Strong lines like “No wonder women are in love with that wonderful Tide” exaggerate, almost mock, the ideal of a woman cheerfully performing the gendered work she has little choice but to partake in. The visuals mirror the same domestic joy.

Women are also portrayed directly in relation to the family: representing a narrow vision of women’s position as caretakers and servants of the household. Their performative happiness feeds into the fantasy that women are naturally inclined to this role, and should be happy to fulfil it.

Hoover took a similar approach with this Christmas ad. The ad speaks directly to husbands, who are the primary audience for the purchase of the vacuum and the fantasy that their wives exist as servants of the home who would be happy to celebrate the holidays with a new tool related to this role.

In the 1970s, the Volkswagen brand expanded on a similar messaging strategy, reworked to fit the era. Their station wagon ads (although these were cars marketed towards families) subtly condescended to women. Volkswagen makes it clear that men are their primary audience by speaking about women rather than speaking to them. Lines like “If you can sell her on this, you can sell her on anything” assume a male reader and reinforce a hierarchy where men are insiders and decision-makers, and women are obstacles in their way.

As a result, the minimalist but captivating tone the brand is known for aligns itself with masculinity, alienating women from being insiders to the brand’s world or equal decision makers in the household.

The line “mommy’s big helper” also speaks down, shifting gears from the car’s technical features to invoking an idealized image of a cheerful, dutiful housewife. It may seem like a wholesome image, but when examined in context, it becomes apparent that it’s rooted in a gendered fantasy that serves male power.

Both Tide and Volkswagen both perpetuate gendered roles within the family in subtly different flavors based on the social scripts of the time. Tide reflected cheerfulness and service as ideal feminine virtues, and Volkswagen reflected a similar message expanding upon it by framing condescension toward women as humor.

The archetypes of accessory, housewife, and the masculine individualist set a default template for how gender shows up in brand storytelling today. These narratives outlived any one product or brand identity, embedding the era’s gendered ideas into the foundation of branding, in turn entrenching them into culture itself.

In the next installment of Gender and Brand, we’ll explore examples of brands trying to push back against these established scripts—and what it means to tell a story that truly diverts from these foundations.

Izzy Colón is a culture writer, creative copywriter, and Contributing Writer for The Subtext. She lives in Chicago, where she spends as much time collecting stories as she does writing them.