For much of modern political history, authority was recognized through established rhetorical forms, using the humble technology of the sentence and the learned discipline of finishing a thought. Political skill revealed itself through a certain agility: an ease with pacing, sequencing, modulation, and vocabulary. To sound authoritative was to suggest that thought had been properly rendered into language capable of carrying judgment, reason, and restraint.

Power arrived less through verbal force than through tactical form.

This model of diction still exists, in the measured discourse of Mahmood Mamdani, for instance. It now competes, however, with another, less disciplined mode, one that draws its appeal from a different force altogether: the popular appetite for candid, unrehearsed authenticity. The obvious example here is Donald Trump, who, by breaking every rhetorical rule and every small arrogance of the English language, has helped usher in a new political dialect, at least in the United States. It is simple, affect-laden, and improvisational. By now, few are surprised by political speech that resists coherence, traffics happily in unsubstantiated claims, or produces utterances that manage, with frightening efficiency, to separate language from its meaning.

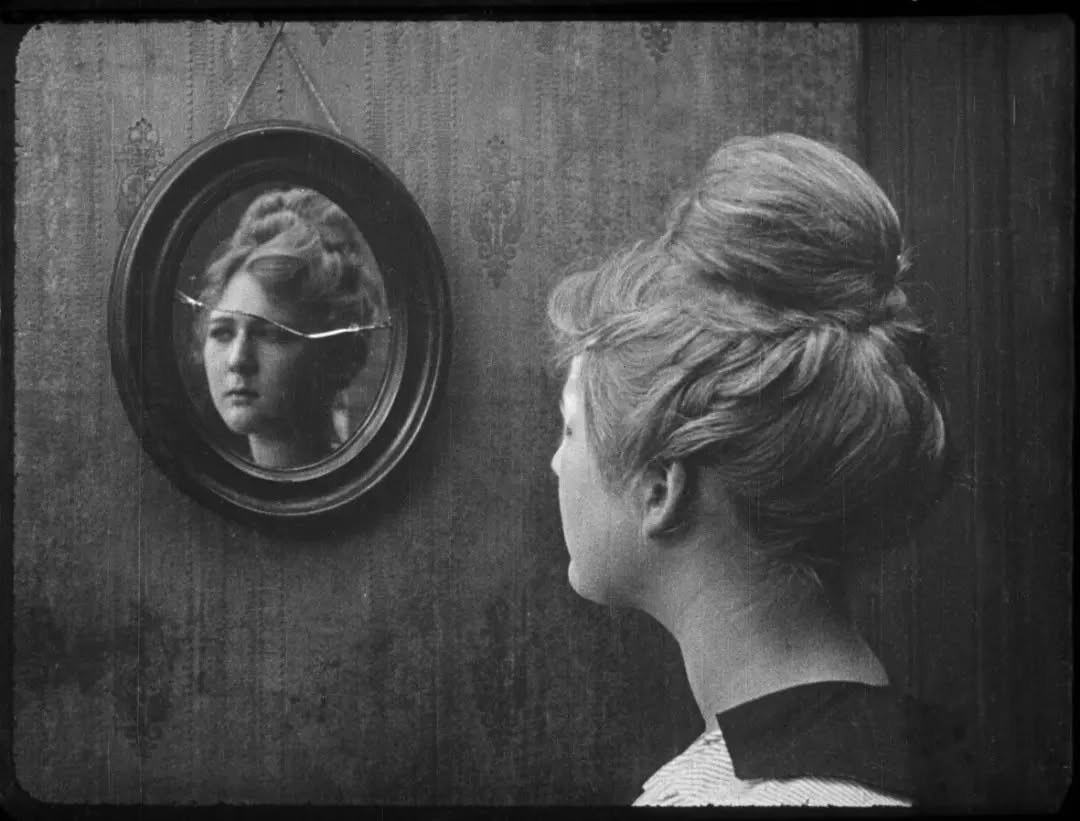

The contemporary division of political languages is often folded into debates about populism, the decay of decency, and, more recently, diagnosis of dementia. What tends to get lost, at least to me, is the more interesting question: what happens at the point where authenticity collapses into style.

We talk about authenticity in language and culture constantly. We scrutinize tone, register, and familiarity: whether speech sounds conversational enough, vernacular enough, relatable enough. We argue over doxa, idiom, and sociolect. What we rarely linger on is idiolect, the particular grain of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, reference, and habit that distinguishes one speaker from another. A distinctive idiolect establishes a stable way of moving through language, a consistency that allows an audience to feel oriented even when the content might lose them.

It is tempting to read rhetorical style as a direct expression of ideology or socio-political position. Increasingly, though, political language seems shaped less by a speaker’s class of origin than by their class of consumption: the media they inhabit, the platforms that train their attention, the forms of speech that absorb and repeat them. Language evolves under conditions of use, calibrated to the rhythms, durations, and rewards of particular media environments.

Trump’s idiolect, beyond the invectives we are all familiar with, is marked by extreme parataxis, shallow syntactic structures, pronoun drift, and heavy deixis (“we,” “they,” “you”). His speech resists grammatical closure, favoring self-repair, ellipsis, and rhythmic redundancy. Clauses pile up. Ideas sit side by side without explanation or hierarchy. A description of the Revolutionary War: “Our Army manned the air, it rammed the ramparts, it took over the airports, it did everything it had to do.” Even if there were airports in 1770, the sentence would still be doing something other than describing history. The effect is a kind of verbal stream of consciousness, with much of the appeal residing in the apparent absence of a speechwriter’s fact checking or restraint.

Mamdani’s discourse runs in the opposite direction. It is hypotactic and historically grounded, built from long syntactic arcs, delayed predicates, low metaphorical density, and careful lexical distinction. Where others reach for moral adjectives like unjust, violent, or cruel, he prefers causal verbs such as produced, administered, differentiated, and institutionalized. His authority rests on specificity and mediation: citation, temporal framing, historical analysis. His sentences perform a steady operation, naming as political what liberal language treats as neutral—citizen and subject, native and settler, custom and law—forcing categories to disclose their assumptions rather than pass as givens. His rhetoric appeals to the intellect and, in the process, puts moral vagaries on trial. “The central question is not Islam, but political violence.”

This model of political language is classical in both a figurative and literal sense. Authority, authorship, and authenticity were foundational to classical rhetoric, the practice of persuasive communication that emerged in ancient Greece as a discipline of law. Rhetoric developed alongside changing conditions in property law, particularly in the late fifth century BCE following the Peloponnesian Wars, when war, exile, and return unsettled the status of land and ownership. Possession alone no longer settled questions of right. In property trials, competing claims had to be made publicly and persuasively. Rhetoric became a civic technology for adjudicating legitimacy, with juries asked to decide less who held land than whose account of origination and transfer could be made to sound convincing.

That authority, authorship, and authenticity are semantically entangled is therefore more than a curiosity. All three trace back to the Latin verb augēre: to increase, to grow, to originate, to bring into being. To author was to bring something into the world; authenticity named the condition under which that origination could be trusted. This sits apart from the root meaning of power, which concerns capacity and coercion rather than intelligibility. In classical rhetoric, authority was earned through persuasion, by shaping language carefully enough to make claims believable.

How that shaping happens at the level of sentence structure is often misunderstood. Parataxis and hypotaxis are routinely mapped onto intelligence in crude ways, as though one signals instinct and the other intellect, chaos versus reason. Literary theory offers a kinder account. Parataxis produces the sensation of thought in motion, ideas stacking side by side like open tabs, each leading elsewhere without resolution. Hypotaxis organizes relation, clarifying sequence, causality, and emphasis through subordination. Both resemble real cognition. Human thought arrives in fragments. Spoken language follows suit. Interviews, conversations, and political rallies rarely unfold in polished sentences with tidy conclusions. Fully sequenced, perfectly subordinated speech remains an ideal, and a somewhat artificial one.

This structural difference becomes newly consequential when viewed through the lens of media circulation. What Roland Barthes described as the distinction between encratic and acratic language maps neatly onto the conditions under which political speech now travels. Encratic discourse aligns with established power, reproducing sanctioned forms and rhythms that assume stable contexts and shared rules of interpretation. Acratic language slips outside those norms, favoring immediacy, repetition, rupture, and affect over closure. Contemporary media environments tend to reward language that moves quickly, survives fragmentation, and generates response without insisting on resolution. Under those conditions, acratic styles circulate more efficiently than encratic ones, not for ideological reasons so much as practical ones.

Seen this way, the present confusion around authenticity becomes easier to understand. If authenticity still means anything here, it has little to do with warmth or relatability. It no longer names sincerity or truthfulness so much as endurance. Voices acquire authority by repeating themselves successfully, by learning which kinds of language platforms will tolerate and amplify. For better or worse, rhetoric now survives less by its gifts of persuasion than by learning how to behave under the conditions in which it travels.

Genevieve Ross is Creative Director at Stocksy and a writer on art and culture. Her essays and criticism have been published in Artforum, Aperture, TIME, VICE, and other publications.

For much of modern political history, authority was recognized through established rhetorical forms, using the humble technology of the sentence and the learned discipline of finishing a thought. Political skill revealed itself through a certain agility: an ease with pacing, sequencing, modulation, and vocabulary. To sound authoritative was to suggest that thought had been properly rendered into language capable of carrying judgment, reason, and restraint.

Power arrived less through verbal force than through tactical form.

This model of diction still exists, in the measured discourse of Mahmood Mamdani, for instance. It now competes, however, with another, less disciplined mode, one that draws its appeal from a different force altogether: the popular appetite for candid, unrehearsed authenticity. The obvious example here is Donald Trump, who, by breaking every rhetorical rule and every small arrogance of the English language, has helped usher in a new political dialect, at least in the United States. It is simple, affect-laden, and improvisational. By now, few are surprised by political speech that resists coherence, traffics happily in unsubstantiated claims, or produces utterances that manage, with frightening efficiency, to separate language from its meaning.

The contemporary division of political languages is often folded into debates about populism, the decay of decency, and, more recently, diagnosis of dementia. What tends to get lost, at least to me, is the more interesting question: what happens at the point where authenticity collapses into style.

We talk about authenticity in language and culture constantly. We scrutinize tone, register, and familiarity: whether speech sounds conversational enough, vernacular enough, relatable enough. We argue over doxa, idiom, and sociolect. What we rarely linger on is idiolect, the particular grain of vocabulary, syntax, rhythm, reference, and habit that distinguishes one speaker from another. A distinctive idiolect establishes a stable way of moving through language, a consistency that allows an audience to feel oriented even when the content might lose them.

It is tempting to read rhetorical style as a direct expression of ideology or socio-political position. Increasingly, though, political language seems shaped less by a speaker’s class of origin than by their class of consumption: the media they inhabit, the platforms that train their attention, the forms of speech that absorb and repeat them. Language evolves under conditions of use, calibrated to the rhythms, durations, and rewards of particular media environments.

Trump’s idiolect, beyond the invectives we are all familiar with, is marked by extreme parataxis, shallow syntactic structures, pronoun drift, and heavy deixis (“we,” “they,” “you”). His speech resists grammatical closure, favoring self-repair, ellipsis, and rhythmic redundancy. Clauses pile up. Ideas sit side by side without explanation or hierarchy. A description of the Revolutionary War: “Our Army manned the air, it rammed the ramparts, it took over the airports, it did everything it had to do.” Even if there were airports in 1770, the sentence would still be doing something other than describing history. The effect is a kind of verbal stream of consciousness, with much of the appeal residing in the apparent absence of a speechwriter’s fact checking or restraint.

Mamdani’s discourse runs in the opposite direction. It is hypotactic and historically grounded, built from long syntactic arcs, delayed predicates, low metaphorical density, and careful lexical distinction. Where others reach for moral adjectives like unjust, violent, or cruel, he prefers causal verbs such as produced, administered, differentiated, and institutionalized. His authority rests on specificity and mediation: citation, temporal framing, historical analysis. His sentences perform a steady operation, naming as political what liberal language treats as neutral—citizen and subject, native and settler, custom and law—forcing categories to disclose their assumptions rather than pass as givens. His rhetoric appeals to the intellect and, in the process, puts moral vagaries on trial. “The central question is not Islam, but political violence.”

This model of political language is classical in both a figurative and literal sense. Authority, authorship, and authenticity were foundational to classical rhetoric, the practice of persuasive communication that emerged in ancient Greece as a discipline of law. Rhetoric developed alongside changing conditions in property law, particularly in the late fifth century BCE following the Peloponnesian Wars, when war, exile, and return unsettled the status of land and ownership. Possession alone no longer settled questions of right. In property trials, competing claims had to be made publicly and persuasively. Rhetoric became a civic technology for adjudicating legitimacy, with juries asked to decide less who held land than whose account of origination and transfer could be made to sound convincing.

That authority, authorship, and authenticity are semantically entangled is therefore more than a curiosity. All three trace back to the Latin verb augēre: to increase, to grow, to originate, to bring into being. To author was to bring something into the world; authenticity named the condition under which that origination could be trusted. This sits apart from the root meaning of power, which concerns capacity and coercion rather than intelligibility. In classical rhetoric, authority was earned through persuasion, by shaping language carefully enough to make claims believable.

How that shaping happens at the level of sentence structure is often misunderstood. Parataxis and hypotaxis are routinely mapped onto intelligence in crude ways, as though one signals instinct and the other intellect, chaos versus reason. Literary theory offers a kinder account. Parataxis produces the sensation of thought in motion, ideas stacking side by side like open tabs, each leading elsewhere without resolution. Hypotaxis organizes relation, clarifying sequence, causality, and emphasis through subordination. Both resemble real cognition. Human thought arrives in fragments. Spoken language follows suit. Interviews, conversations, and political rallies rarely unfold in polished sentences with tidy conclusions. Fully sequenced, perfectly subordinated speech remains an ideal, and a somewhat artificial one.

This structural difference becomes newly consequential when viewed through the lens of media circulation. What Roland Barthes described as the distinction between encratic and acratic language maps neatly onto the conditions under which political speech now travels. Encratic discourse aligns with established power, reproducing sanctioned forms and rhythms that assume stable contexts and shared rules of interpretation. Acratic language slips outside those norms, favoring immediacy, repetition, rupture, and affect over closure. Contemporary media environments tend to reward language that moves quickly, survives fragmentation, and generates response without insisting on resolution. Under those conditions, acratic styles circulate more efficiently than encratic ones, not for ideological reasons so much as practical ones.

Seen this way, the present confusion around authenticity becomes easier to understand. If authenticity still means anything here, it has little to do with warmth or relatability. It no longer names sincerity or truthfulness so much as endurance. Voices acquire authority by repeating themselves successfully, by learning which kinds of language platforms will tolerate and amplify. For better or worse, rhetoric now survives less by its gifts of persuasion than by learning how to behave under the conditions in which it travels.

Genevieve Ross is Creative Director at Stocksy and a writer on art and culture. Her essays and criticism have been published in Artforum, Aperture, TIME, VICE, and other publications.